“Really bad. … Really bad.”

That was the response I got from water policy veteran Kathy Ferris when I asked how bad things could shake out in negotiations on Colorado River management. Ferris was a leader in the negotiations and development of Arizona’s 1980 Groundwater Management Act and currently serves on Gov. Katie Hobbs’ Water Policy Council.

In a recent phone call on the topic, ASU water expert Sarah Porter nearly mirrored Ferris’ words.

“Things could end up… not good… very not good.”

It’s not a question of whether negotiations will be hard on Arizona — only a matter of how hard.

“The impacts are going to be meaningful,” says ADWR Director Thomas Buschatzke. “They are going to have some pain attached to them.”

“There are going to be losers,” says Sharon Megdal, Director of UofA’s Water Resources Research Center.

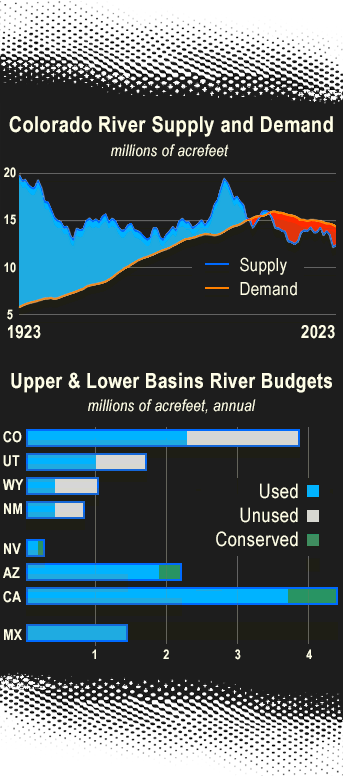

The Colorado River is overallocated. Demand outweighs supply. One hundred years ago, when the basin states were figuring out how to budget shares of the River’s water, it had been unusually rainy in the Southwest and they overestimated average annual flows. And their budgets didn’t calculate for the water lost to evaporation as it sits in storage reservoirs.

Add in the recent 20-year drought and you’ve got a serious water supply problem.

Add in growing populations and commercial water needs in all seven basin states and Mexico, and you’ve got a serious demand problem.

Then contend with a system of historic priorities to the River water, differing interpretations of existing River law, and 100 years of interstate litigation, and you’ve got a serious political problem.

Hopefully the states can work something out. They have until the end of next month to do so.

If they don’t, we may see the federal government take waters into their own hands — something all the states want to avoid because it means someone won’t be happy, and that means more lawsuits and more uncertainty.

Today’s story will be the first in an ongoing series looking more closely at what’s at stake for Arizona in the battle for the Colorado River’s water supplies. Why could things get “very bad”? And for who? What are the arguments from various states? And the proposed solutions?

But we’ll start with Arizona Water 101, covering some of the big picture views of how water works — and doesn’t work — in our state and in today’s world of growing water scarcity.

Water is the new everything

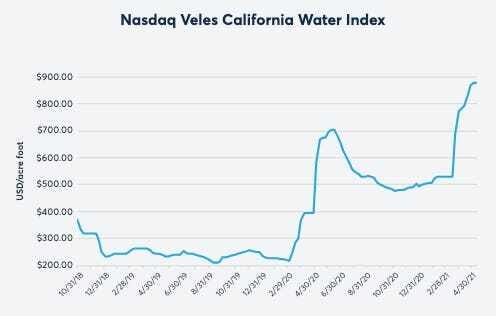

Around the world, water is being called “the new gold” and “the new oil.” The stock markets are paying more attention to water’s value and futures trading has already kicked off. In California, the value of water doubled from 2018 to 2021.

Last year, Congress proposed a ban on water futures trading, saying it incentivizes investors to manipulate prices for a resource that is too important to be treated as a commodity.

“They could, for example, buy water rights to drive the price up so that they can then make money on the futures market,” says Mary Grant of Food and Water Watch.

In Texas, a lawsuit between cities will go to court next month, disputing a $1 billion water-pumping project.

“We’re going to fight this thing until the end,” said Bobby Gutierrez, the mayor of Bryan, Texas. “It effectively drains the water source of the cities.”

Saudi alfalfa growing operation Fondomonte is asking Arizona courts to throw out Attorney General Kris Mayes’ lawsuit, which alleges that the company’s water use is a “public nuisance.” Meanwhile, using water to grow alfalfa has been outlawed in Saudi Arabia because it has become… a nuisance.

They say that the best way to make money during a gold rush is to start selling shovels. Here in Arizona, water districts are being bought up and consolidated by private companies from as far away as West Virginia and Canada.

But the commodification of groundwater resources can be dangerous. Since Roman times, courts have upheld that essential resources like water and air belong to the public, to be managed by the state for the public’s benefit.

Tensions between the benefits of free market principles and the basic right to affordable, clean water will grow as the resource becomes more scarce.

To sum things up, a quote from the Phoenix and Maricopa County Board of Trade, back in 1885:

“In desert countries like the valleys of Arizona, water is king, and he who owns or controls it becomes dictator, and rules even the cultivator of the soil.”

Where does it come from, where does it go

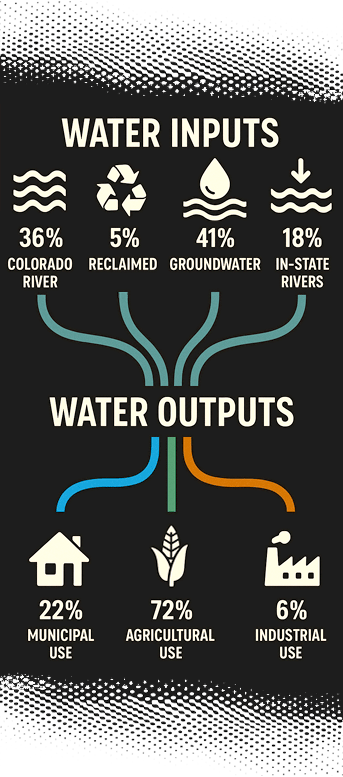

Colorado River water makes up 36% of Arizona’s water resources. And it doesn’t just go to agriculture. Phoenix depends on the River for 40% of its water supply.

In Arizona, we need water to drink, to generate electricity for air conditioning, to grow 90% of the nation’s leafy greens during the winter months, to keep sports fields covered with grass, to stream movies over the cloud, and, of utmost importance: for flushing toilets.

As a basic consumer protection, new housing developments in central Arizona need to have an assured supply of water, a policy which has led to a freeze on development in the Pinal and Phoenix AMAs, and which is now being litigated by homebuilders and pro-growth think tanks.

We need water for basically everything in life. And Arizona’s supply is limited and diminishing. That’s why any further reductions to our Colorado River apportionment will weigh heavily on the state.

Why is it a battle?

If water in Lake Mead continues to deplete, eventually the Hoover Dam will stop producing electricity, and then water will stop flowing through the dam altogether — a situation called “deadpool.”

And with current levels of drought and water use, that eventual depletion is guaranteed.

The Upper Basin states, especially Colorado, have tighter water policies, requiring reductions in River water use during years with less rainfall and snowpack. According to the most recent reports from the Bureau of Reclamation, those states are collectively using about 55% of their apportioned share of River water.

The Lower Basin states, after recently agreed-upon cutbacks borne largely by Arizona, are using about 77% of their share. That percentage would be higher but some River water conservation has been subsidized with money from the Inflation Reduction Act — money which might not be available in the future.

The Lower Basin states are willing to accept further cutbacks to their water use, but they also want the Upper Basin states to, at least, freeze their current levels of water use.

The Upper Basin, however, wants room to grow its water demands along with their growing populations and economies. It’s the Lower Basin states, they say, who are overusing the River and should be responsible for needed cutbacks.

Arizona’s position

No matter how a deal is cut, Arizona is going to get hit the hardest. Under the proposal put forward by Arizona, California, and Nevada, Arizona would be required to cut back its River water use by around 760,000 acrefeet — 27% of its original apportionment. Those cuts would mainly impact CAP canal water users like Phoenix, Tucson, and Tribal communities.

California would see a 10% cut and Nevada a 16.5% cut.

The goal is to balance supply and demand by bringing the River’s original 16.5 million acrefoot water budget closer to 12 million acrefeet.

But if the Upper Basin states grow their water use, that would mean more cuts to the Lower Basin to keep the budget balanced. The Lower Basin states aren’t keen on that idea.

The Law of the River

It’s nothing new that Colorado River water is a limited resource. Serious discussions over its future management began in 1919 with the formation of the League of the Southwest among basin states.

Our deserts were seen as land ripe for agricultural development. “Just add water” was the mindset.

Negotiations and policy have developed over a century, resulting in a body of law and U.S. Supreme Court rulings collectively referred to as “The Law of the River.”

Arizona’s current cutbacks were stipulated by agreements in 2006 and 2019, but those agreements expire next year. The federal government, which operates the River’s dams and manages flows, needs to have a new plan ready to implement by a late-2026 deadline. The basin states have until the end of next month to submit a joint proposal to be considered by the Bureau of Reclamation in their management plan development over the next year.

And what happens if the states don’t come to agreement?

No one can say for sure. But many, many lawyers will be involved.

A new sense of “nuisance”: Lawyers for Fondomonte, the Saudi company that runs an alfalfa mega-farm and is constantly under fire for pumping huge amounts of groundwater, told a judge that they should be allowed to keep doing what they’re doing, Capitol scribe Howie Fischer reports. Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes sued Fondomonte last year, calling the company’s groundwater pumping a “public nuisance,” an untested legal strategy. Fondomonte says state law presumes agricultural operations with good practices do not constitute a nuisance.

Not having it: Gov. Katie Hobbs has vetoed seven water-related bills that she said provided “political cover” for the Legislature, KJZZ’s Camryn Sanchez reports. All of the bills were sponsored by Rep. Gail Griffin, a Republican from Cochise County who has long held the keys to Arizona’s water legislation. Hobbs said the bills made “pointless trivial statutory changes,” when Arizonans want actual groundwater management.

Long time coming: After 25 years, a contaminated aquifer in central Phoenix was finally cleaned up last week, KTAR’s Balin Overstolz McNair reports. The aquifer, which is located in an industrial area, was contaminated by tetrachloroethene (PCE), a chemical often used in the dry-cleaning business. Back in 2016, state officials started putting microbes and sucrose into the ground, which began the process of breaking down the harmful chemicals. Arizona’s Department of Environmental Quality has another 37 sites scheduled for decontamination efforts.

Mexico taps out: Under threat of tariffs and sanctions, Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum has agreed to immediately deliver Rio Grande water to Texas and is calling for further negotiations on how to manage water delivery obligations under prolonged drought conditions. At home, she’s facing accusations that she’s delivering more water than is required.

Two out of seven ain’t bad: A recent study shows that, among the seven Colorado Basin states, Arizona gets the silver medal in recycling wastewater, at a rate of 52%. Nevada gets the gold at 85%, and there’d be enough new water for 2 million homes if all the other states raised recycling rates to 40%, say the UCLA researchers.

Slow the bleeding: The Arizona Department of Water Resources has proposed that the goal of the newly established Willcox AMA should be to reduce the area’s groundwater overdraft by at least 50% over the next 50 years. The Willcox Basin is currently overdrafting its aquifer at a roughly 3:1 rate. The 50% reduction, if achieved, would mean the basin is only using twice as much water as it can sustainably afford to. Some say the goal is too lofty, while others say it's literally a half-solution at best.

The proposed Willcox AMA goal: “To support the long-term viability of the regional economy, mitigate land subsidence, and extend the life of the aquifer by reducing groundwater overdraft by at least 50 percent by 2075.”

Listen in:

Willcox city officials and local wine growers share their perspectives on groundwater scarcity and AMA regulations with Christopher Conover on The Buzz.

Joanna Allhands and Elvia Diaz from the Republic talk with KJZZ’s Mark Brodie about proposed legislation to save water by banning “non-functional turf.”

UofA’s Amy Barber talks with senior research specialist Dr. Vanessa Buzzard about how urban water conservation impacts ecosystems and wildlife.

And Kyle Paoletta, author of American Oasis: Finding the Future in the Cities of the Southwest, talks with Streetsblog about the early development of cities like Phoenix and how water is a main character in those stories.

“I write in the book that, like, the entire history of Phoenix is running out of water and then needing to get more water,” Paoletta says.

Watch closely:

The Green Desert is a new documentary from PBS looking at how the Colorado River powers agriculture in Arizona and the Southwest.

ASU has uploaded recordings of the panel discussions from its recent Rethinking Water West conference, including talks on Arizona’s water, energy, and land futures, and the private consolidation of Arizona’s municipal water systems.

Arizona’s Family Investigates looks at the resurgence of uranium mining across Arizona and the risk it poses to water supplies.