We would be remiss this week if we did not address the 75 million acre-feet elephant in the room: The states of the Colorado River basin have blown past a federal deadline to draft plans for how to share the river’s water amid severe drought and a warming planet.

We’ll spend most of this issue exploring just that topic.

But to start, we thought it might help to bring the issue home by talking to someone who isn’t a governor or river commissioner or otherwise directly involved in negotiations.

Earlier this week, I interviewed Elston Grubaugh, the general manager of the Yuma-area Wellton-Mohawk Irrigation and Drainage district, which technically lies in Gila County but gets Colorado River water from the Imperial Dam. While I was asking him specifically about his hopes for the somewhat controversial intentionally created surplus program in future Colorado agreements — something we’ll get to in a future issue — I also asked his thoughts on the failure of the states to reach a deal.

And who better to ask than someone who lives where the river really does run through it.

Here’s what he said. I think it’s revealing:

“I think we (the district) are disappointed,” Grubaugh told us. “This wasn’t new. People started in 2023 knowing that things needed to be accomplished by the end of 2026, and here we are. If you’re a landowner or grower and you want to buy a new Case or John Deere or other brand of tractor, and you want to finance that for a bit, or the neighbors farm across the road comes up for sale and you want to buy it, you have to deal with lenders who are intelligent and up to date on things (and thus know there’s no agreement on the Colorado). We and everyone else would like some certainty. The clock is running.”

Grubaugh said he wishes the feds had been more hands-on throughout this process. (Incidentally, this sentiment maps with a Politico piece we shared a couple weeks back — the Trump administration, stakeholders say, has been surprisingly hands-off, at least until now.)

“Some of us are old and gray and ugly and remember the process for the 2007 guidelines. The folks from Reclamation were strong personalities, could play good cop, bad cop, and could harangue the basin states into an agreement,” he said. “The BOR and DOI staff are now very engaged. And they’re probably as frustrated as anyone. Will they dictate something? I don’t know, but we’re hopeful that a plan arises from the ashes, so to speak.”

In other news, Grubaugh said, it’s been raining for days in Yuma, and oddly enough, area farmers would like it to stop so they can harvest.

Now back to the nuts and bolts.

Negotiations have been playing out for years, and the current set of Colorado agreements expires in late 2026. But the states have made little progress. That’s part of the reason why the feds told state negotiators that if they didn’t come up with a preliminary plan by Nov. 11, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum would intervene.

The prospect of the federal government dictating an agreement between the states is potentially legally iffy, and even representatives from the Interior Department have indicated that they’d much rather have the states reach a deal themselves than have to impose terms.

There have been some signs of daylight — earlier this fall, Arizona Department of Water Resources chief Tom Buschatzke said the states may find some agreement on a supply-based scheme for sending water downriver. But those plans seem to have fizzled out, and Nov. 11 came and went with no deal and no announcement of federal action.

That said, the states and feds expressed some cautious optimism — though we’ll see how well-founded that feeling is — that the parties could reach an agreement, and thus that negotiations will continue, for now.

“The seven Colorado River Basin states together with the Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Reclamation recognize the serious and ongoing challenges facing the Colorado River,” reads a joint statement issued last week by the states, Interior and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. “While more work needs to be done, collective progress has been made that warrants continued efforts to define and approve details for a finalized agreement.”

Negotiators from Utah struck a particularly optimistic tone. Gene Shawcroft, Utah’s Colorado River commissioner, told reporters last week that the states found “conceptual agreement on a framework” that was enough to forestall federal intervention, per the Salt Lake Tribune.

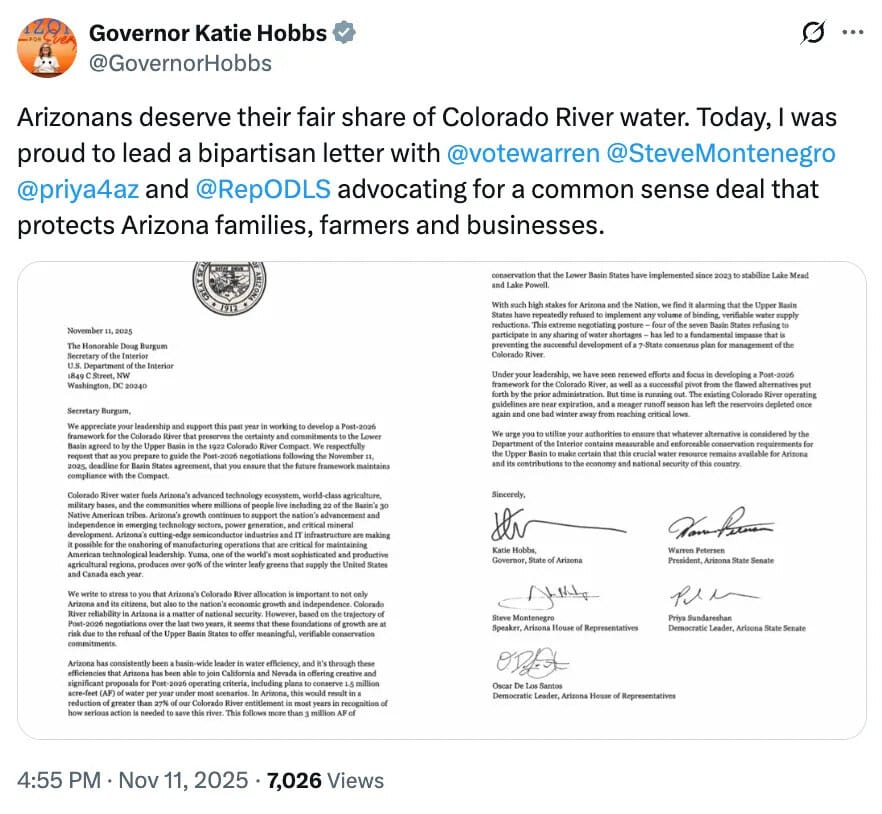

Down the river, Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs and other local leaders are asking the feds to step in.

In particular, Hobbs wants Interior to ensure that the upper basin states of Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico and Utah make cuts that guarantee a certain level of water delivery to the lower basin states of Arizona, California and Nevada.

“We urge you to utilize your authorities to ensure that whatever alternative is considered by the Department of the Interior contains measurable and enforceable conservation requirements for the Upper Basin to make certain that this crucial water resource remains available for Arizona and its contributions to the economy and national security of this country,” Hobbs wrote in a letter to Burgum last week.

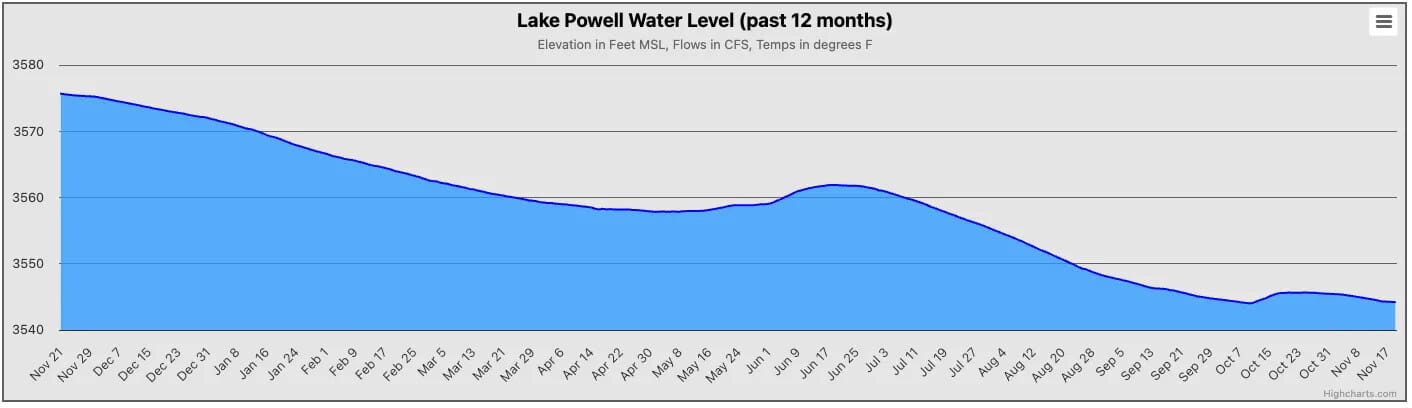

Indeed, without action and if projections for a dry winter come true, water levels in Lake Powell could be too low to generate power by the end of December 2026 — an end-game scenario all parties want to avoid. The reservoir has faced a similar crisis before, which officials addressed with emergency releases from other reservoirs. But that’s not a sustainable long-term strategy, and failure to reach a deal — in other words, reverting to a 1970s regulatory scheme — won’t make avoiding dead pool any easier.

To give you a sense of the bipartisan reach of the issue, Hobbs was joined on the letter by Democratic and Republican state legislative leadership — including Warren Petersen and Steve Montenegro, GOP leaders who are suing the state over a new program that will allow subdivisions to be built in the Phoenix exurbs if water providers agree to diminish groundwater pumping.

We’ve talked a lot about the different elements of Colorado talks in this newsletter before, but in case you need a quick refresher on the core dispute:

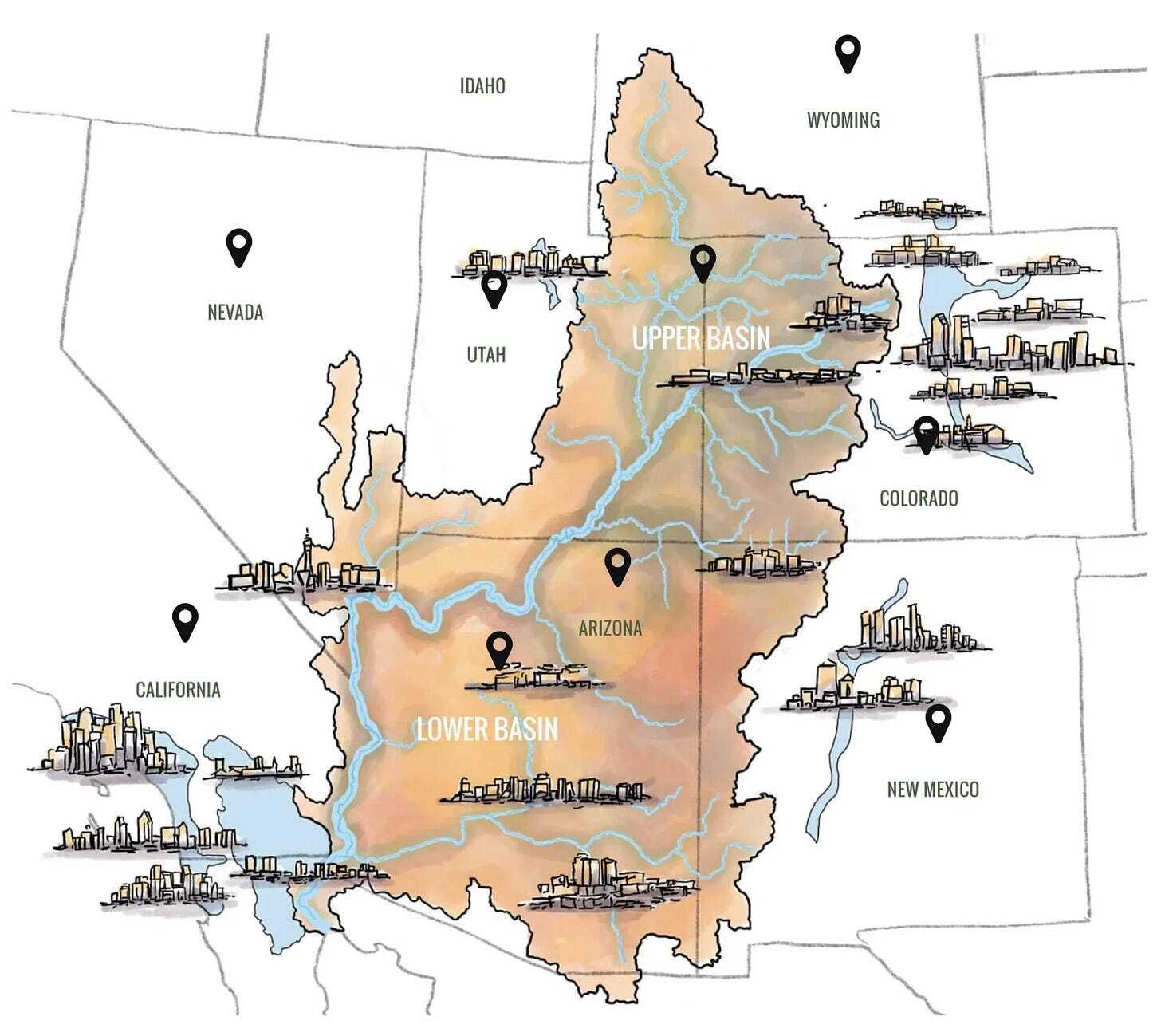

Basically, it’s a problem of geography, economy and differing interpretations of the 1922 Colorado River compact. Right now, the lower basin states contain the bulk of the basin’s population and economic activity. But the headwaters of the river lie in the upper basin. And the two halves of the basin disagree over whether the 1922 compact requires upper basin states to deliver a certain amount of water downriver — the interpretation favored by the lower states — or simply not to deplete a certain volume of water.

The upper basin states argue that depletion in river levels is the result of climate change and poor snowmelt, not consumption, and thus that they shouldn’t be obligated to make further cuts to enable growth and economic activity in the arid southwest.

Hobbs and other Arizona leaders have been hammering the line that the upper basin states are refusing to accept necessary cuts, effectively holding the lower basin hostage and forcing the bulk of the reduction downstream, even as we’ve faced repeated cuts already.

(In case you’re curious, read Article III of the Compact here and tell us what you think. The main provision is that “the States of the Upper Division will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75 million acre-feet for any period of ten consecutive years.” Many in Arizona would say that it clearly requires the Upper Basin to deliver water downriver. Many in Colorado or Wyoming would say the compact isn’t so clear on that point.)

Hobbs is right that upper basin negotiators don’t seem inclined to accept cuts. Colorado’s negotiator, Becky Mitchell, told local stakeholders this month that she couldn’t commit to a certain level of cuts from her state because of the precarity of the natural water supply.

“I have no idea what Mother Nature is going to do to any of you in this room this year,” she said at a conference with water professionals, per Colorado Public Radio.

Colorado talks also involve stakeholders from Native American tribes and Mexico. Jason Hauter, a member of the Gila River Indian Community and an attorney for the tribe in the negotiations, told High Country News that part of the problem with the Colorado is the chronic overallocation that has resulted from the use-it-or-lose-it model of prior appropriation.

“The Western legal system was designed to encourage development. The prior appropriation system is really about rewarding those that develop their water the fastest,” he told HCN. “But you can only keep developing water if there is plenty of water in the system.”

WIFA makes contact: The Water Infrastructure Finance Authority board, the state body tasked with using public dollars to procure alternate sources of water for Arizona, voted this week to help private companies develop water desalination plants in California or Mexico, among other water projects, per Capitol Media Services’ Bob Christie. The body did not vote on a controversial proposal from water provider EPCOR that may have involved importing water from the Mojave Desert.

“These are real projects, this is no longer a hypothetical,” Chelsea McGuire, WIFA’s executive director, told reporters, per Christie. “This is no longer something that someone is dreaming of in a room somewhere.”

Winter wonderland: The state, particularly central and Southern Arizona, has been pounded by precipitation this week. In Wickenburg and Tonopah, rescue crews bailed out drivers trapped in cars on flooded roads. Valley residents, meanwhile, saw 1-inch hail pile up in their yards and driveways. Videos of the hail almost make it look like it snowed on the highway — though from my view, it looks more like soap overflowing from a dishwashing machine. The hail also caused flight delays at Sky Harbor and partially collapsed the ceiling of a West Valley mall, per the Republic’s Jose R. Gonzalez.

ADAWS gets a day in court: Litigation over the state’s new Alternative Designation of Assured Water Supply rules — which we have detailed before here and here — has been winding its way through the courts for months. Last Friday, lawyers for the state and the plaintiffs — Republican legislative leaders and the Home Builders Association of Central Arizona — met in court to debate the state’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, which argues the state overstepped its bounds in promulgating the rule without legislative approval, per Courthouse News’ Joe Duhownik

“The legislature is certainly smart enough to understand that there is a water problem in Arizona,” attorney Emily Gould, representing the association and the lawmakers, said during the hearing. “If they wanted to redefine assured water supply to cover over some historic overdraft, they could have specifically authorized the department to do so. And they simply did not.”

Here’s an image that neatly encapsulates the wonky politics of water in our conspiratorial, MAGA-fied country, featuring Republican Utah Gov. Spencer Cox.