For two years, the state has blocked developers from building new homes in parts of the Phoenix area that would primarily be serviced by groundwater — a valuable resource in short supply.

But last month, officials cracked open the door for new construction for the first time, issuing an “Alternative Designation of Assured Water Supply” (ADAWS) to a West Valley water provider that can service tens of thousands of new homes in fast-growing cities like Buckeye and Surprise, focal points for Arizona’s urban water crisis.

The fundamental hydrological realities haven’t changed. There isn’t enough groundwater in the area to ensure new homes built there will have access to water for the next 100 years, as required by law.

Instead, the state created a workaround that will allow new residential construction to resume.

On Oct. 7, EPCOR, a Canadian utility company with customers in suburbs around the Valley, became the first provider to receive an ADAWS designation. The designation opens a path for the development of around 60,000 homes, and ensures that many more already in the provider’s network have some confidence about their future water supply.

“This ADAWS designation is going to save water, it is going to support sustainable economic growth, and it is going to create more housing,” Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs said in statements to the press last month.

ADAWS is a complicated mechanism. But basically, when Hobbs announced a moratorium on new development within the Maricopa and Pinal AMAs in 2023, it meant that developers couldn’t rely on groundwater there to satisfy their requirement that they have a “100-year assured water supply.”

The rules allow water providers to count existing groundwater withdrawals toward a designation of assured water supply if the provider also pledges new water supplies. In exchange, the provider must reduce groundwater withdrawals by 25% of the volume of new water it’s bringing online.

The actual rule is here, starting on page 26, if you’re confident in your legalese. And EPCOR’s agreement with the state is here.

EPCOR is pledging a total of about 14,400 acre-feet per year in new water supplies in the form of water from the Central Arizona Project, surface water from the Agua Fria river, and treated effluent stored in recovery wells. And it’ll reduce groundwater pumping by 3,600 acre-feet per year, a sum that could increase if the company acquires other alternate water supplies in the future.

(For context, the state says an acre-foot of water can supply an average of three Phoenix-area households).

The designation allows EPCOR to assure its existing customers of continued water availability, and opens the door for it to add new ones to its rolls — the 60,000 new homes it can now support, at least on paper. And even the designation itself is valuable.

“It’s kind of like getting a gold star that you can tout to people that maybe might want to be in your service area,” said Kathleen Ferris, a member of the governor’s water policy council and former director of the state Department of Water Resources who helped craft Arizona’s landmark 1980 Groundwater Management Act.

Already, developers are looking to take advantage of the designation.

Harry Elliott III, of Elliott Homes, told the Republic’s Sasha Hupka that the firm would soon begin development of a master-planned community in Waddell. The ADAWS program is open to would-be providers in the Phoenix and Pinal active management areas, both of which have been subject to years-long development moratoria. The state expects other regional cities and providers, including Buckeye, Queen Creek and Arizona Water Company to seek ADAWS status as well.

It was technically possible for providers to obtain new water supplies before ADAWS, but with the state’s “unmet demand” finding, in effect, they’d have to rely almost exclusively on that new water to receive a designation, an often prohibitively expensive and legally complicated process. Groundwater is simply cheaper.

The state also has an incentive here. The requirement for assured water supplies only applies to subdivisions. But there are lots of other uses that strain our groundwater. Plus, the state is looking for creative ways to regulate pumping in the absence of a new legislative solution.

“It’s important to understand that without a designation, EPCOR could continue to serve new groundwater,” Ferris said. “They couldn’t serve new subdivisions, but they could serve data centers, industry, apartments, all these kinds of things. The theory is that a designation is a better way of managing how our limited water supplies are used.”

In order to get an ADAWS designation, providers must also join the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District (CAGRD), which replenishes the groundwater its members mine with other renewable supplies of water.

But state rules allow providers to use a certain amount of groundwater — a “groundwater allowance” — before the replenishment obligations kick in. The size of that allowance is based on 2023 water deliveries, and providers can for the most part choose how to use it. Some providers might blow through the allowance in the first several years of the designation while they bring new water online. Others might spread the allowance over a longer time frame. The only caveat under ADAWS is that providers must support new developments with new water supplies before using groundwater.

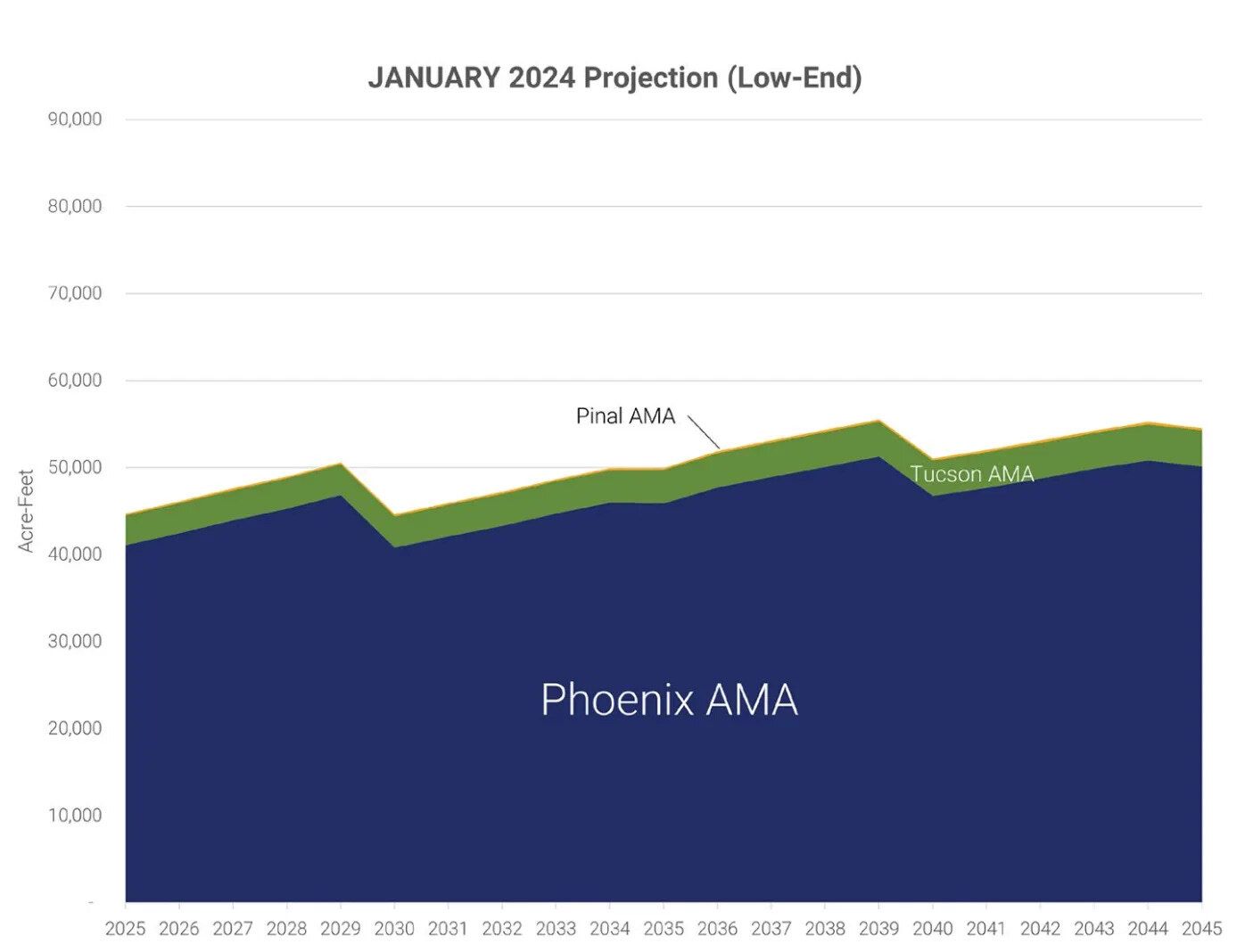

In theory, the new rules should reduce the groundwater district’s replenishment obligations in the long run, as existing and new subdivisions served by providers with an ADAWS designation reduce their groundwater pumping and incorporate other sources of water. CAGRD predicts the ADAWS rules will shift its obligation from member lands — individual subdivisions that enroll in the district — to member service areas that receive water from a designated provider, which tend to recur smaller obligations.

This is all a potential boon for taxpayers living in CAGRD, who owe a replenishment assessment to the district on their tax bills. (That’s a lot of people — CAGRD’s footprint in Pinal and Maricopa counties contained more than 280,000 individual lots as of 2024).

“Although somewhat counter-intuitive, the faster an ADAWS provider grows, the quicker the CAGRD obligation diminishes as that provider acquires alternative supplies,” CAGRD staff wrote in the district’s draft 2025 plan of operation.

This is all important because it’s increasingly difficult for anyone, CAGRD included, to find new water, leading to greater reliance on long-term storage credits and other forms of paper water, Ferris said. And there’s the looming prospect of further cuts to Arizona’s share of Colorado River water.

That conundrum is illustrated in a recent report from researchers at Arizona State University about the district.

“When CAGRD was established, it was assumed there would be sufficient excess CAP water to meet CAGRD’s replenishment obligations through 2046,” the report says. “That assumption proved incorrect as enrollment radically outpaced this supply and other entities with long-term CAP contracts used more and more of their rights.”

Not all are on board

The ADAWS program was developed over the course of 2023 and 2024 by the governor’s water policy council, drawing hundreds of comments from providers, cities, academics, builders and environmental groups. The state initially proposed that participants would reduce groundwater by 30% of new water supplies, but dialed back the requirement to 25% — cities like Buckeye had asked for that number to be 15%.

But, as we’ve discussed here before, home builders and their allies in the state Legislature have problems with the plan.

In March, Republican legislative leaders Warren Petersen — himself a homebuilder — and Steve Montenegro sued the state, arguing the new rule was hastily and improperly adopted without adequate stakeholder input and economic impact analysis.

They framed the reduction requirement as a tax being unfairly applied to builders and providers without legislative approval, forcing them to “obtain water to compensate for ADWR’s projected deficits caused by the historic uses of other users,” they wrote in the lawsuit. Dialing up the political rhetoric, they called the plan “redistributionist.”

The litigation isn’t exactly surprising — the governor and Republican lawmakers have been unable to come together on major groundwater legislation, despite some initial optimism at the beginning of the last legislative session, which instead saw lawmakers try to (ultimately unsuccessfully) scuttle the ADAWS plan by reining in administrative rulemaking authority.

Homebuilders are also suing to challenge the state’s moratorium on new development in the groundwater-dependent outer reaches of the Phoenix and Pinal AMAs. A judge has yet to rule on either case.

On the flip side, some lawmakers and water experts have questioned whether ADAWS does enough to reduce groundwater pumping. State Sen. Priya Sundareshan, a Democrat from Tucson and the Senate minority caucus’ water whiz, wrote in a comment on the rulemaking last year that the state should restore the 30% reduction, instead of 25%.

The Arizona chapter of the Sierra Club took issue with one of the core premises of the program — that existing groundwater usages can be grandfathered in. If developers can’t build in an area because of insufficient groundwater, they, well, shouldn’t, the Sierra Club’s Sandy Bahr wrote in a comment on the rule.

Bahr also expressed concern that CAGRD would become responsible for replenishing more groundwater withdrawals than it can bear if providers who receive ADAWS designations do not transition away from groundwater quickly enough.

“This proposal is more of the same old story when it comes to water management in Arizona: ‘grandfather in’ all the unsustainable uses that got us in trouble in the first place, and then when the oft-touted GMA actually does what it is supposed to do and reins in new, reckless, and unsustainable development, make the CAGRD responsible for addressing the impacts of growth,” she wrote.

This Tuesday is the provisional deadline for the seven Colorado River basin states to come to an agreement for long-term management of the river’s water resources.

The plan has to be in place by Oct. 1, 2026, but the Trump administration has said that failure to reach a deal by next week will lead to federal intervention.

It’s not clear what effect the deadline is having on negotiations. A spokesperson for the Arizona Department of Water Resources declined to comment on the state of play or make DWR chief Tom Buschatzke available for an interview on the subject because of the increased sensitivity of negotiations ahead of the Nov. 11 deadline.

Gov. Katie Hobbs, speaking at a meeting of the National Water Resources Association Meeting Leadership Forum in Tucson this week, said upper basin states need to be prepared to take cuts to their share of the river, not just expect the lower basin states to shoulder the brunt of reductions, per the Daily Star’s Tony Davis.

“This river is shared by seven states, and it benefits seven states. Therefore there must be water conservation efforts in all seven states within the Colorado River Basin,” Hobbs said, per Davis. “Yet as I stand before you today, after years of negotiations and meeting after meeting after meeting, and time running short to cut a deal, we have yet to see any offer or real, verifiable plan to conserve water from the four Upper Basin States who rely upon this shrinking river.”

JB Hamby, chair of the Colorado River Board of California, expressed some cautious optimism in an interview with Politico.

“Impending deadlines motivate action — we are getting to the eleventh hour and there is more opportunity to strike a deal in the final weeks and days than there has been in the past few years,” he said.

We don’t know exactly what federal intervention might look like, though the Politico piece unsurfaced a presentation that Department of Interior officials gave to Native American tribes last month that may offer some clues.

“The presentation outlined in broad strokes a potential ‘federal contingency’ plan for the Colorado River’s operations,” Politico reports. “Descriptions included potential cuts to water use by Lower Basin states, although it also made a pledge that ‘minimum water delivery would be available for essential health and safety purposes.’ It also suggests tapping into a series of reservoirs across Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico.”

A river runs through Trump (or does it?): The impending crisis on the Colorado River “has all the trappings” of an issue that might intrigue President Donald Trump, Politico writes in a new piece titled “The water war Trump hasn’t blown up.” But even with the political importance of the basin states, the opportunity to score points against California Gov. Gavin Newsom and the optics of American infrastructure in decline, the Trump administration’s approach has been “incremental and institutional,” as one water wonk put it.

Pumped up: A new University of Arizona study suggests that human activity in recent decades has depleted Tucson-area aquifers to a much greater degree than variations in the climate. The authors reached that conclusion by reconstructing aquifer conditions going back millennia.

“Since the climactic period known as the Last Glacial Maximum – about 20,000 years ago – precipitation has continuously recharged the aquifer under Tucson, the study concluded,” per a write up of the study from UofA’s Office of Research and Partnerships. “During dry climate periods, less precipitation seeped back into the aquifer, and the water table dropped by as much as 105 feet, compared with the levels in wetter periods. However, modern pumping from the mid-20th century to present day caused twice the drawdown of the water table compared with natural climate fluctuations.

Missed connections: Officials with the Central Arizona Project and Salt River Project are designing a $250 million project to provide two-way connectivity between SRP and CAP canals through a pump-and-pipe system at Granite Reef dam, per KTAR’s Heidi Hommel. Completion is expected in 2028, if all goes to plan.

“It would be another major connection of the two large renewable water sources in the state of Arizona, adding lots of operational flexibility for both of our groups,” CAP Assistant General Manager Darrin Francom told Hommel.

Arizona’s growing fast, and every new bridge, school, and neighborhood we build should reflect the best of us.

That means hiring skilled local workers, paying them fair wages, and giving them careers they can be proud of. When we invest in people, the work lasts longer, the projects run smoother, and our communities grow stronger.

Let’s build Arizona’s future with dignity and pride — and make every job one worth keeping.

Learn more at Rise-AZ.org.

ASU researchers surveyed Yuma residents about their water consumption.

The number one issue? The taste of Arizona’s very hard tap water.

The researchers assured Yumans that the water is nevertheless safe to drink, and suggested “bottled water as an alternative to the kitchen faucet for drinking water if Yuma County residents don’t like the taste of hard water,” according to a KTAR report on the survey.