A new report from a series of non-governmental organizations situated along the Colorado River offers a startling finding: There’s no water available.

This week, we sat down with Kyle Roerink, the executive director of the Nevada-based Great Basin Water Network, to get a new perspective on Colorado talks from a neighboring state and to learn why his group and the other authors on the report offer such dire predictions on the future of water in the Southwest.

There’s no more water. Or at least, that’s the contention of a new report from a series of non-profits from across the Colorado River basin.

The authors say that as states negotiate the future of the river — a process that’s playing out slowly and not-so-surely, with a November deadline from the feds looming in the background — they need to keep in mind that its waters are dramatically overallocated and climate change is making things worse.

This doesn’t only mean water-smart policy. It means a new mental and social framework for thinking about the river.

“The indisputable evidence of drier times ahead illustrates a few simple conclusions,” the report reads. “All parties currently using water must commit to using less than they have in the past.”

To put it another way: The seven river states collectively claim 15 million acre-feet a year in Colorado River water. But actual river flows average about 12.5 million acre-feet annually.

Rectifying this broken algebra means, per the authors, foregoing new dams and other diversions, reducing both agricultural and residential water use, respecting indigenous water rights and other basin-wide curtailments.

This week, we sat down with Kyle Roerink, the executive director of the Nevada-based Great Basin Water Network and one of the report’s authors, to get a new perspective on Colorado River talks from a neighboring state and to learn why his group and the other authors on the report offer such dire predictions on the future of southwestern water.

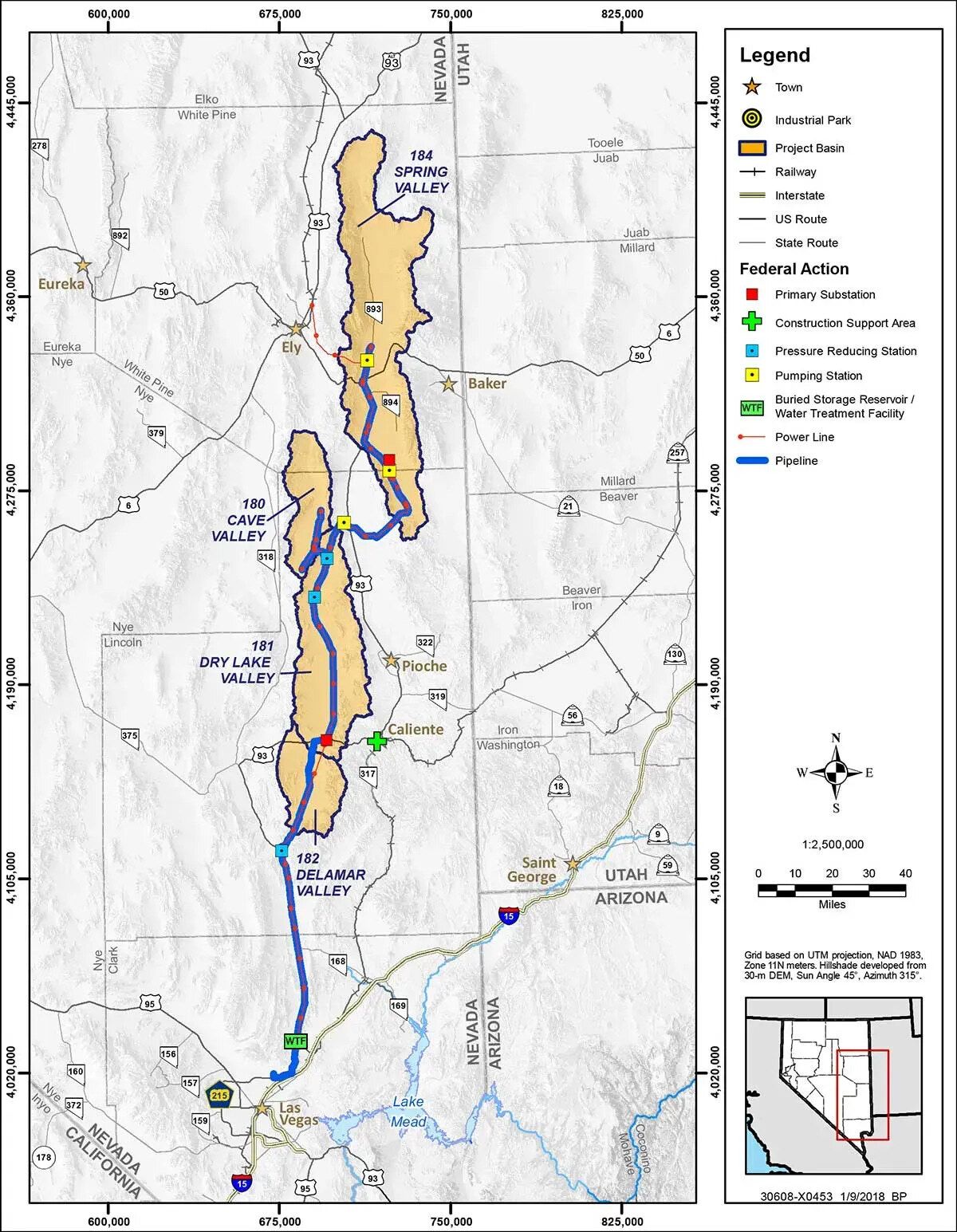

Great Basin Water Network in particular coalesced around opposition to a plan from the Southern Nevada Water Authority to pump and pipe waters from the Great Basin 300 miles to Lake Mead, crossing watershed boundaries, in order to fuel growth in Las Vegas.

The SNWA abandoned those plans, and Roerink says other states should follow Nevada’s example and learn how to innovate in times of scarcity.

We’ll let you read the report for yourself here. In the meantime, here’s our conversation with Roerink, lightly edited for clarity and concision.

WA: Can you start by telling us a little bit about Great Basin Water Network, its history and the work it does today?

KR: Our organization works on water rights issues throughout the southwestern U.S., largely in Nevada and Utah. But on Colorado River issues, we take a big picture look.

The genesis of our organization was spurred out of a groundwater importation effort led by Las Vegas. We had to sue them for over 20 years to stop them from importing groundwater from the Great Basin watershed into Lake Mead, and throughout that time, it was really clear that everything, all roads lead to the Colorado River system.

The best way to describe what informs us is the fundamental tenets of Western water law. While not perfect, there are some key provisions that, if water managers throughout the West actually lived by them and abided by them and respected them to the fullest extent, I believe we would be in much better shape.

The reason the report is titled “There’s No Water Available” is, if you look at the bedrock provisions of water law, water actually has to be available for an appropriation to be made.

So as we are seeing and dealing with entities that are applying for more water in any given state that would come out of the Colorado system, collectively, I think it’s fair for us to ask, is there actually water available? We’ve lost 20% of surface water flows since the turn of the 20th Century.

You mention these fundamental tenets. How are they not being respected?

It goes beyond the Twainian ideal of it all (“Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over”). There are provisions explicitly written in state statutes across the West that you can’t negatively impact someone else’s rights, this whole notion of conflict is essential.

But most of the states are not respecting these bedrock principles of availability in trying to limit conflict. That’s the really scary thing. What’s troubling, especially in the upper basin, there’s an effort to develop more and more as quickly as possible in order to get these rights. But the problem isn’t the system that allows people to ask for water, the problem is that regulators are appropriating the water.

So, we at the Agenda hear lots about Arizona’s position on Colorado talks, naturally. What’s the view from Nevada?

The view from Nevada is that if more states were doing what Nevada was doing, we’d be in a much better place.

Largely, we’ve done two things that I think are outliers. One is that we have become the global model for urban conservation. Some of that, we have inherent advantages because of our proximity to Lake Mead. There are also some funding streams that can give us that advantage. But largely, that happened because Las Vegas doesn’t have a giant groundwater pipeline. Out of scarcity, certainly, should come innovation.

The other thing that we have done, at the state level, we have recognized surface water and groundwater connectivity as being something that regulators have to consider.

One interesting note in this report is that it says cities should curtail their use. I think a lot of people in the water world point to agriculture as the real drain on water supplies, and say cities are acting relatively responsibly given their needs. You’ve probably heard of the ag-to-urban legislation in Arizona. How does your report complicate that narrative?

There was a report that came out, the Great Salt Lake watershed, that watershed imports somewhere between 10% and 20% of its water from the Colorado River. You could save 400,000 acre-feet of water a year by ripping up turf and green lawns.

The reason why municipal conservation is low-hanging fruit is big municipal water providers have the ability to incentivize conservation of water. Whether we like it or not, agriculture is viewed largely as a backup for municipalities, something that, if enough money is thrown their way, farmers will give up their water.

But with that comes ecological problems, community problems, and I think the Salton Sea (in California, which saw precipitous declines when Colorado water was diverted to support urban development in the Southwest) is a place to look at what happens when you have Colorado River scarcity: impacts to children, impacts to wildlife, impacts to their economy.

If we want to take agricultural water, we have to be prepared for that to happen. If we want to fix those places, if we believe that those places have a right to exist, it’s going to cost all of us, all taxpayers, a lot of money. Not only do you have to pay for the water, you also have to pay for mitigation.

Just to play devil’s advocate, lots of municipal lawns and golf courses and whatnot are watered with reclaimed or wastewater, right?

One thing that makes Nevada kind of an outlier is we can treat that water and then send it to Lake Mead for return flow credits and use it again. The point is we have the technology where we can take that and you can treat it to a level where it can be in someone’s tap tomorrow rather than on a golf course.

That’s kind of the argument that some opponents of the Project Blue data center down in Tucson made, if you’re familiar with that case, right? Like, there is technology to reduce or even eliminate net consumption, but why shouldn’t we be putting that technology to use for other needs?

Right. We can give water to data centers, mines, farmers, whoever else, or should we be conserving our water in a way so that ratepayers aren’t having to foot a massive bill for major industrial projects, just to serve their basic needs?

I won’t foreclose on the ability of technology to help assist us. I think data centers and AI are indicative of one fact we can’t get around: New technology usually requires a lot of water, one way or another, whether it’s an indirect use or a direct use.

Until there’s a technology that makes water out of air without stealing the weather from someone else, I’m gonna say that the cheapest and most reliable way to find stability is to do what we recommend.

Crossing our fingers and hoping the tech moguls of the world will save us won’t work.

So, should we be afraid?

I don’t think we should be afraid. I think we should be excited and hopeful to meet a challenge. While the 20th Century was defined by our industriousness in building things, the 21st Century will be defined by our ability to reimagine things.

More to the moratorium: Development of almost half a million homes in fast-growing towns like Buckeye and Queen Creek is on pause because of the state’s moratorium on new construction in certain areas primarily serviced by groundwater, per Tony Davis in a piece in High Country News that examines the hydrologic history of Phoenix’s prodigious sprawl. That’s more homes on pause than policymakers and builders have previously acknowledged.

“State officials and local governments like Buckeye’s have routinely enabled this kind of growth through zoning and planning policies that treat sprawl as a way of life,” Davis writes. “Homes built within the urban core typically use less land, consume less water and require less infrastructure. Although they’re more expensive to build due to land costs, their urban location preserves desert habitat. But development on the edges has long been seen as the quickest, simplest way to meet people’s housing needs.”

Alternative pathways: Arizona officials say they have awarded the first designation of assured water supply under its new and not uncontroversial alternative pathway rule to EPCOR, catalyzing, at least in theory, residential development in the West Valley, per KJZZ’s Camryn Sanchez.

You mad?: Yuma officials have approved a resolution opposing a potential transfer of Colorado River water from southwestern Arizona to Queen Creek, per KYMA’s Eduardo Morales.

“We lose these fights, these are the fights that end the way of life in Yuma, or any of these smaller communities along the river,” said Yuma Mayor Doug Nicholls, per the report.

Ignorance isn’t bliss: The Salt River Project has installed a new kind of hydrologic flume in northern Arizona to measure how snowmelt makes its way down to the Valley’s water supply (or doesn’t), KTAR’s Heidi Hommel reports.

“We plan to copy and paste this into other watersheds. And we want to do it in the Salt and even the Cragin watershed,” Zachery Keller, an SRP hydrographic scientist, said.

The Pinal puzzle: Pinal County is in an awkward position as both a frontier of exurban development from Phoenix and for the generally low-priority rights held by its farmers, who have already suffered major cuts to their allocations. The view from Pinal County these days? Not so great, says Coolidge lawmaker and Senate Natural Resources Committee chair T.J. Shope, per Pinal Central’s Noah Cullen.

“The negotiations are so far apart at this point in time between the northern and southern states and I don’t know that there is a bridge to be built,” Shope said.

After our interview with Rep. Alex Kolodin back in June, we couldn’t help but make some final remarks, as they were pertinent to another story in that edition:

Kolodin, in our Drip Line conversation, provides another perspective: Foreign-owned farmland is no longer an issue once water becomes a free market commodity, because residential water users in central Arizona will simply outbid foreign companies.

He could be right about that — or it could be that wealthy, water-scarce countries won’t give up their Arizona water, even if the buyout price is generous.

A follow-up question for Kolodin — and I’ll certainly publish any response from him — would be whether we want to see how high the cost of water is driven up in an open water market. It could become an incredibly expensive game to play, hitting citizens much harder in the pocketbook.

As promised, here is Kolodin’s response: