Fondomonte is fighting back.

In court filings this week, the Saudi-backed farm — mired in controversy for sucking up southwestern Arizona groundwater to grow alfalfa for export back to the Kingdom — asked a judge to throw out state Attorney General Kris Mayes’ lawsuit against the La Paz County farm.

Their motion questioned Mayes’ authority to bring a nuisance complaint and sought to block discovery while the court considers the farm’s arguments.

“The Court should not allow the Attorney General to use Arizona’s public nuisance statute as a backdoor to regulatory powers she does not possess,” attorneys for Fondomonte, which is represented by the high-powered Rose Law Group, wrote this month.

A judge has yet to rule on the motion to toss the case.

Indeed, Mayes’ strategy is novel, to say the least.

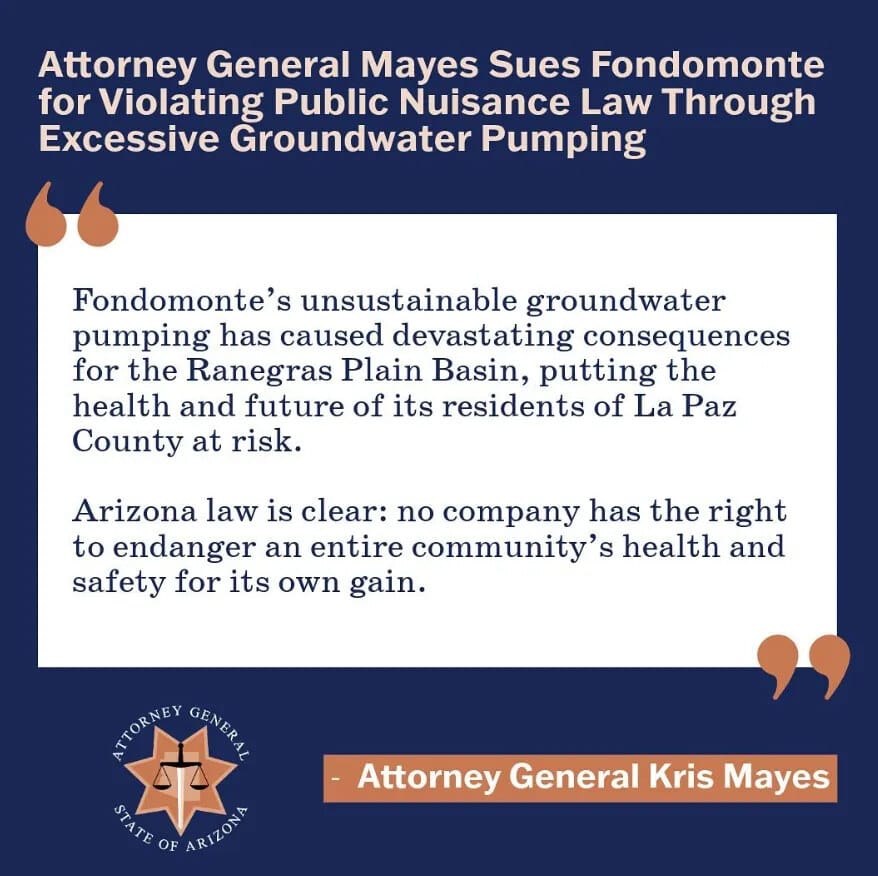

As we wrote in the very first edition of the Water Agenda, she sued Fondomonte in late 2024, alleging the firm was using something like 80% of the Ranegras Plain Basin’s groundwater supplies, drying up wells in neighboring communities and causing the land to sink.

But Fondomonte isn’t breaking any water laws — groundwater pumping in the Ranegras Basin, like most of the state, is effectively unregulated. So Mayes is arguing that the company’s “excessive” pumping constitutes a nuisance.

“Since Fondomonte began operating within the Ranegras Basin, dewatering of the Ranegras Basin has accelerated at an extraordinary rate, threatening the water supply upon which every resident within the Ranegras Basin relies,” she wrote in a December filing. “The substantial and rapid decline in the Ranegras Basin’s groundwater level caused by Fondomonte’s massive groundwater extraction has widespread effects and is a public nuisance, harming everyone reliant on the Ranegras Basin for water.”

But Fondomonte says that’s bunk.

Attorneys for the farm argue Mayes is looking for a “backdoor” to exercise regulatory authority over groundwater pumping that she doesn’t possess.

When the Legislature passed the Groundwater Management Act in 1980, it designated regulatory powers solely to the state Department of Water Resources, not the attorney general or anyone else.

Even if her office had the authority, lawyers for Fondomonte say the attorney general doesn’t have the subject matter expertise to regulate in this area.

Mayes, they argue, seeks to repackage “the regulatory remedies of the GMA as a public nuisance action and [ask] this Court to impose restrictions that the ADWR has declined to pursue.”

Were the lawsuit stripped of its public nuisance label — a mere pretext, Fondomonte argues — it would be clear that it is in fact a regulatory action, according to the filings.

While Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Scott Minder considers this argument, Fondomonte has also asked to stay discovery — the process through which parties in a civil matter exchange evidence.

“Fondomonte Arizona should not be forced to participate in expensive and disruptive discovery and disclosure pending a dispositive motion based purely on the law,” attorneys for the firm wrote.

In other words: We don’t want to produce evidence if a judge is going to throw the case out.

The parties have since agreed to a partial stay, under which Fondomonte must respond to a request to produce evidence the state made in July, but no responses from subsequent requests are due.

The novelty of Mayes’ approach is not exactly a secret.

She has been open about the fact that she’s suing in part because lawmakers have failed to pass comprehensive groundwater management reforms for years, despite bipartisan outcry from officials in rural counties worried about rapidly declining groundwater supplies.

Lawmakers did try to strip her of her ability to go after groundwater pumpers through the nuisance statute once she started discussing her ambitions to do so, but Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs vetoed those bills.

Mayes says as much in her complaint:

“This case is the result of a legislative failure to address a water crisis with catastrophic effects on the groundwater level in the Ranegras Basin.”

But that argument is unconvincing to some, and downright odious to others, who fear that if Mayes is successful, there will be nothing to stop her from going after other groundwater pumpers — including domestically owned farming operations — with similar lawsuits.

The presence of a Saudi-owned firm pumping groundwater to grow hay in the desert to feed cows in Saudi Arabia — in part because wells supporting alfalfa operations in Saudi Arabia itself had already run dry — first came to the public’s attention in 2015, following a report by the Center for Investigative Reporting.

At the time, some state officials, including current ADWR chief Tom Buschatzke, told the public that the concern was overblown — in essence, these were new owners of an existing operation, and that all industry and agriculture uses water, some more than others, regardless of whether they’re based in Riyadh or Phoenix or Wilmington, Delaware.

Fondomonte made similar arguments in its initial January response to Mayes’ lawsuit. Fondomonte has actually been lauded for its water efficiency, its lawyers said. And anyway, Mayes can’t possibly know exactly how much water they’re pumping, precisely because this is an unregulated basin.

Along the same lines, the state can’t define “excessive pumping” without that information, they argue. And either way, Fondomonte attorneys say its wells make up “a small percentage” of the total number of wells in the basin.

But concern about the operation continued as neighboring wells dried up. And as our own Christian Sawyer argued earlier this year, even if every farm operation pumps groundwater like there’s no tomorrow, regardless of nationality, it matters who profits at a time of continued shortage and great uncertainty over the future of the Colorado River.

“Should Arizona be going to other drought-stricken communities and using their water to grow alfalfa that we ship back to Arizona?,” Sawyer wrote. “Would those communities be exclusionary or xenophobic if they said ‘Sorry, Arizona, but you can’t take our water — we actually need it?’ Or, would we find those objections sound and reasonable?”

A royal purchase: Officials from the town of Queen Creek — a fast-growing suburb southeast of Phoenix — are continuing on their quest to reduce reliance on a dwindling supply of groundwater by pursuing another purchase of water from the Harquahala Valley 80 or so miles out of town. The Arizona Republic’s Maritza Dominguez reports that the Queen Creek Town Council approved a plan to purchase the rights to 1.2 million acre feet of water from the Harquahala over the next 100 years for $240 million.

The state had already approved plans from Queen Creek and fellow exurb Buckeye to acquire water from the Harquahala. Moving the water across basins — usually seen as bad water policy — is possible because the Harquahala and a handful of other sites were designated by lawmakers decades ago as a possible source for water transfers to other communities. The Harquahala in particular works as a site in part because its proximity to the Central Arizona Project canal.

What this all means is developers would no longer have to obtain individual assurances of supply in order to build in Queen Creek — they’d be able to leverage the town government’s designation, as builders in Phoenix and other big cities are able to do. Remember that the state has blocked developers in Queen Creek and Buckeye from building if they’re relying on groundwater.

We have more background on the transfer here.

Cooked: Ted Cooke, the former general manager of the Central Arizona Project, is no longer being considered to lead the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The Trump Administration withdrew his nomination last week following complaints from states in the upper basin of the Colorado River worried about the positioning of the Bureau in the case of federal intervention in Colorado River talks, which is seeming increasingly likely, Alex Hager, from Colorado-based KUNC, reports.

“I’ve since learned from other folks that I know, and I know lots of people, that that reason was pretty much a BS reason to basically get me out of the running,” Cooke said. “Because there were certain objections that had been raised from some of the states with which I would be dealing.’”

A nutty situation: Excessive groundwater pumping in the San Simon valley is drying up wells and causing the earth to sink — what’s known as subsidence, everyone’s favorite hydrologic phenomenon. One big reason for this, reports the Republic’s Clara Migoya, is a boom in nut farming in the region in recent years, particularly for pecans. Now, even enterprising pecan farmers are asking the state to step in and regulate irrigation and groundwater pumping in the basin, a not uncontroversial proposition for growers who would see their operations dry up without access to that sweet subterranean nectar.

Pack it in, pack it out: The Nogales Ranger District is asking visitors to the Madera Canyon campground and recreational area in the Santa Ritas to bring in their own water and not rely on potable water supplies at the campground or picnic area because of persistent drought, according to KVOA’s Hector Barragan.

Sometimes, more water is not the solution.

The University of Arizona is evacuating 30 students from the Arizona-Sonora dorm because of flooding caused — at least according to a video circulating on campus — by someone striking a fire sprinkler with a water jug.

Flooding reached from the building’s 8th floor to the basement, per KGUN’s Jacqueline Aguilar. Some students will be unable to get back to their rooms for weeks.