Perhaps no two cities better represent the state of growth in Arizona than Buckeye and Queen Creek.

These far-flung communities — former cowtowns and railway stops home to only a few thousand people not so long ago — exploded in size in recent years, with cheap land giving way to massive subdivisions to feed Arizonans’ growing appetite for housing (and air-conditioned, suburban convenience).

In Buckeye, frequently named the fastest growing city in the country, local leaders are anticipating 300,000 people by 2040, and perhaps more than a million if all master-planned communities in the area are fully built out.

But this growth has depended on access to groundwater, a dwindling resource.

That reality came to the fore when Gov. Katie Hobbs took office in 2023 and ADWR released updated groundwater calculations in the Phoenix Management Area which led to the state placing a moratorium on development in the two communities, much to the chagrin of local homebuilders and civic leaders (as we covered here recently).

But now, the state has authorized a transfer of thousands of acre-feet of agricultural groundwater from the Harquahala Groundwater Basin to Buckeye and Queen Creek.

Buckeye will be allowed to withdraw 5,926 acre-feet per year for up to 110 years and Queen Creek up to 5,000 acre-feet per year for up to 110 years.

The transfer allows the cities to augment and diversify their water supplies, helping get the assurance necessary to facilitate more growth.

But it does not automatically restart housing construction, nor resolve the lawsuits that builders have brought against the state over its groundwater modeling and construction moratorium.

The cities still need to invest in the treatment and transportation infrastructure to actually get the water to the Phoenix management area. They might also consider becoming designated water providers, rather than relying on water companies or individual developments to get the necessary certificates of assured water supply.

In the meantime, though, Buckeye and Queen Creek leaders have heralded the transfer as a “significant development” and “incredible milestone.”

“This agreement will support and expand the city’s water portfolio and ensure the sustainability of not only our community, but also the economic vitality of the region and the entire state of Arizona,” Buckeye Mayor Eric Orsborn said in a statement the Governor’s Office released last week. “Buckeye remains committed to providing safe, reliable water far into the future, and we are grateful for the hard work and coordination over the last few years to make this a reality.”

The Harquahala holds over 8 million acre-feet of water. The Arizona Department of Water Resources determined that the amount of groundwater depleted under the transfer would be basically the same as with "business as usual" and not cause unreasonable damage to neighboring users.

So how does this all work?

First, while it sounds similar, this is not something that was authorized with the passage of 2025’s ag-to-urban legislation, which allows certain agricultural users to relinquish groundwater rights to development. To the contrary, this transfer has been years in the making.

It’s generally bad water policy (and against the law) to transfer groundwater across watershed boundaries, especially from rural areas to urban (or urbanizing) ones. Farmers, understandably, are sensitive to the potential of losing their water to developers. And — to use a favorite water policy phrase — it can look like robbing Peter to pay Paul, leveraging the future and shifting water around to cover gaps in supply without actually addressing the underlying shortage.

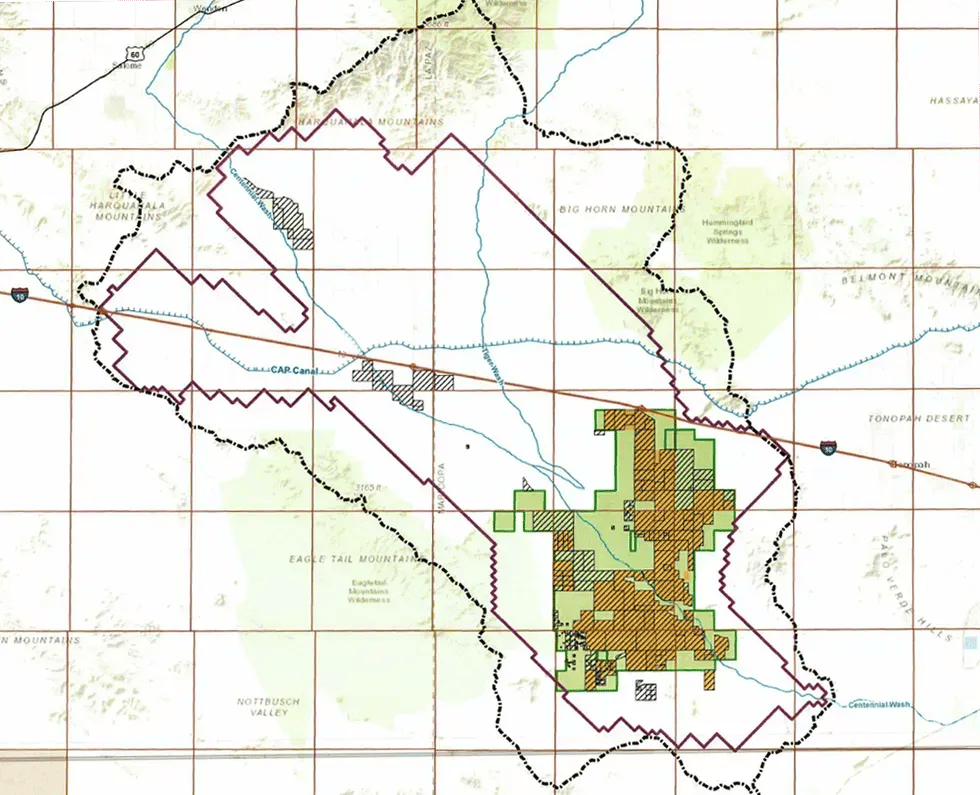

But decades ago, state lawmakers designated the Harquahala and a handful of other basins as sources for a potential water transfer. (The controlling statute, which explains the mechanics of a transfer in greater detail than I can comfortably accommodate in this space, is here.)

In the years since, as the Arizona Republic pointed out in its reporting, private companies have been buying land and water rights in the basin with the anticipation of one day selling the rights to cities or water companies.

The Harquahala Basin, in particular, works for this deal because of its access to the Central Arizona Project canal, allowing water to be transported to the Valley without having to construct a whole new pipeline.

That said, the water would need to be treated before being sent through the canal, as law firm Gammage and Burnham pointed out in a recent blog post, and new water quality standards for the canal are currently pending at the federal level.

The Buckeye and Queen Creek transfers are themselves years in the making.

Both communities applied for the transfer in early 2024, each having recently purchased farmland and associated water rights in the Harquahala — an $80 million deal for Buckeye in February of 2023 and a $50 million deal for Queen Creek around the same time. And the cities had been working with the state to navigate the byzantine requirements of the law for years before that.

The transfer is not a cure-all. Senate Minority Leader Priya Sundareshan, a Democratic water whiz, told Capitol Media Service’s Howie Fischer that the concept of transferring water from one parched area to another is “philosophically wrong,” even if legally above board.

"I don't think it solves anyone's problems really on a permanent basis," she said.

In the Phoenix Management Area, the state is under fire from developers and legislative Republicans for refusing to certify new development in parts of the Valley that rely mostly on groundwater (like Buckeye and Queen Creek).

In the San Pedro River basin, the state is embroiled in litigation for the opposite reasons.

Last month, the Center for Biological Diversity and other local environmental stakeholders sued the state Department of Water Resources, alleging the state was allowing the construction of dozens of subdivisions in the Fort Huachuca and Sierra Vista areas based on inaccurate water supply data.

As a result, homes are sucking up water from the San Pedro — the last free flowing river in the Southwest (meaning no dams are messing with its natural flow).

“Gov. Hobbs and (ADWR Director Tom) Buschatzke refuse to acknowledge that over-pumping in Sierra Vista is violating the San Pedro River’s water rights,” Robin Silver, the co-founder of the Center for Biological Diversity, said in a statement in June. “They refuse to act despite laws requiring review of inaccurate water adequacy designations and consumer protections requiring full disclosure of those facts. So we’re taking Arizona to court.”

The center says that a 2023 ruling from a Maricopa County judge quantifying the water rights for the San Pedro National Riparian Conservation Area means the state needs to review its measurements in the rivershed.

The center and state have gone toe-to-toe in court over the river numerous times, including twice last year — once to get the state to establish an active management area in Sierra Vista, and once to compel the state to review and potentially pull the water supply certificate for a 7,000-unit development.

The first case was dismissed. The state and center settled in the second case, leading to a review of the development’s water.

Now, the center wants to make the state continue this review across the rivershed, forcing Buschatzke “to fulfill his mandated responsibilities to determine that a 100-year water supply is legally and physically available to serve Cochise County subdivisions.”

The state has yet to respond to the complaint in court.

Whiffing on WIFA: This year marked the third in a row in which the state Water Infrastructure Finance Authority saw cuts during the budget process, Chelsea McGuire, the authority’s director, told KJZZ’s Mark Brody last week. Former Gov. Doug Ducey once promised to set aside $1 billion for the authority’s projects, including the possibility of a desalination plant in Mexico.

“If we as a state are a serious partner at the negotiating table with industry — because even $1 billion was not going to be enough, right? — industry is going to have to come alongside and be a partner with WIFA,” McGuire told Brody. “That money was there, symbolic of our commitment to long-term water augmentation. So it was never the amount. It was about the commitment. And so saying, ‘Well, we're not going to commit more money to it until you have a project.’ It's very hard to attract that project and to be a serious partner if the money is not there.”

Expand your palate: Phoenix received $180 million in federal funds for Phoenix’s new North Gateway Advanced Water Purification Facility, which will treat 8 million gallons of recycled water a day, KTAR’s Damon Allred reports. The facility will recycle wastewater into drinking water that’s “so clean it meets or exceeds federal and local drinking water requirements,” per the city.

Mr. Martin goes to the HOA: A Goodyear man has been repeatedly cited and fined by his homeowners association for handing out free cold water to neighbors from a cooler at his house, AZFamily’s Jason Barry reports. The man, David Martin, has refused to pay the fines and instead filed petitions to remove members of the association board. His petition has been thrown out, and Martin is now fundraising for a lawsuit.

“I don’t understand why having a cooler with free cold water in the driveway for part of the day is such a big deal,” Martin said.

There goes the neighborhood: The wildfires that devastated the Grand Canyon’s North Rim, incinerating the historic Grand Canyon Lodge — not the first time it’s burned down, in fact — have also hit the park’s water treatment facility, releasing toxic chlorine gas that can settle down in the canyon, ABC15 reports.

Plumbing for answers: Phoenix is among other large American cities that saw an increase in the number of households without access to water from 2017 to 2021, per a new paper in Nature Cities that Bloomberg Businessweek covered last week. The increase reflects a broader shift: more and more people without access to running water live in urban areas, as opposed to rural ones traditionally associated with that lack of plumbing.

“Low-income Americans, particularly those of color, were forced into more decrepit accommodations, while others fell behind on bills,” Bloomberg’s Laura Bliss and Klara Auerbach wrote. “The urbanization of plumbing poverty accelerated after the 2008 recession, and today 72% of US households lacking running water live in metropolitan areas, more than double the proportion from the early 1970s.”

After months of strained secrecy — which, remind me, we needed that for what purpose? — the City of Tucson has made public new information about the energy and power usage of Project Blue, the data center project whose progress depends on the city approving an annexation petition later this summer.

Now, the Arizona Luminaria is reporting that the end-user of the data center — another closely guarded secret not known even to some of the policymakers tasked with reviewing the project — is Amazon Web Services.

I’m not sure any of the facts and figures in the newly unveiled development agreement or the Amazon revelation are going to make the project’s naysayers much happier.

The agreement again maintains that the project will not only be water neutral — but in fact, water positive through replenishment and investment in new water infrastructure.

But it also suggests that the project could grow to include three data center sites across the region, making it the largest customer for both Tucson Water and Tucson Electric Power.

In the initial stages, the first site would require 440 acre-feet of water a year. The first two sites, though, would require almost 2,000 acre-feet of water per year. That’s about enough for 3,765 homes, per Joe Ferguson at our sister newsletter, the Tucson Agenda.

One big outstanding question was how long the facility would use potable water before its reclaimed water infrastructure came online. The answer? Three years, according to the document.

"This actually isn't draining our water supplies," City Manager Tim Thomure, who supports the project, told the Tucson Sentinel’s Dylan Smith. "We have more leakage than this amount.”

Thomure’s support aside, Ferguson, Smith and others have reported substantial still-lingering skepticism among members of the city council, with whom the decision ultimately lies.

Thomure told Smith at the time that even he didn’t know the end user of the data center, adding, "I can say it's not Dr. Evil.”

If Amazon Web Services (and its owner, Jeff Bezos) is indeed the customer in question here, some might disagree on that point.