In this week’s Water Agenda, we look at a secretive water purchase discussion by the City of Tucson and dive into the complicated world of water marketing.

Yes, there’s a whole water market where public and private entities alike can buy and sell water — or just as often, virtual representations known as “paper water” — for any number of reasons, from ensuring municipal water availability to seeking profit.

It’s a nerdy topic, no doubt, but water marketing (and the related water banking) are important management tools.

And they help illustrate that when we talk about water as a commodity, we’re often talking about something that isn’t quite real in the physical sense.

Also in this week’s issue, please welcome new writer Arren Kimbel-Sannit.

Arren is an Arizonan who comes to us by way of Montana to helm the Water Agenda for the next few months.

What the heck? Let’s do introductions first. It’s only polite.

Water Agenda reporter Christian Sawyer dipped out to take much of the summer off. But before he handed his baby over, he wanted to ensure that I (Arren) was up to the task of managing it for a while.

So Christian subjected me to an “Ask Me Anything” interview this week to get to know me and to better introduce me to the Agenda faithful.

Anyway, here’s a little about me. Reach out with tips, comments, questions, or complaints to [email protected]!

Christian: How long have you been writing? What was your first gig as a journalist and your most recent gig as a journalist?

Arren: I’ve been in the news business since my first internship at Phoenix Magazine the summer after my freshman year of college at ASU, about a decade ago. My first big-boy job was at the Arizona Capitol Times, where I wrote for now-Agenda chief Hank Stephenson and covered the state House of Representatives. Most recently, I was the chief politics reporter for the Montana Free Press, an investigative news non-profit in Helena, Montana.

Christian: What's your history in Arizona?

Arren: While I was technically born in California — a fact I shudder to admit — I’ve spent the majority of my life in Arizona, beginning when my family moved here when I was six months old. I began covering local and state politics here, with a focus on development issues. After a couple years in the gauntlet of the Arizona Capitol, I headed north to Montana, where I covered state government for two different outlets for about five years. (Mercifully, Montana’s Legislature can only meet for 90 days every two years per the rather progressive state Constitution.) Outside of work, I’ve spent more or less my whole life searching for purpose and identity in an ocean of suburban sprawl, often by heading for the hills. What could be more Arizonan — or more specifically Phoenician — than that?

Christian: I know you've been living in Montana — were you seeing headlines over there about Arizona's water situation and the Colorado River?

Arren: I followed Arizona water issues because they were important to me as an Arizonan. But Montana, despite being a headwaters state with a pioneering stream access law, has its own host of water issues — knock-down, drag-out exempt well fights, tribal treaties, nutrient loading in rivers and more. Still, these are two western states with exploding populations (albeit at different scales), both governed by the prior appropriation doctrine of water use. So there are more than a few similarities.

Christian: You’re currently in an environmental studies program. Where are you studying and what drew you to the subject? Are you planning to continue as a journalist after your studies, or contemplating a pivot to another field of work?

Arren: I’m getting a master’s degree in environmental studies from the University of Montana. While my interests have more to do with the political, economic and philosophical theories of the environment than they do with, say, taking water quality samples out in the field, my research — which is generally Arizona or Phoenix focused — gives me the excuse to explore the built and natural environments in the West from different angles. After this, I’d like to pursue my PhD. But so long as I can continue to draw a modest income from journalism, I won’t ever be too far away from a newsroom.

Christian: Which Arizona water stories are currently on your radar that you're hoping to cover while you're at the Water Agenda?

Arren: I’m most interested in the effects of residential and commercial development on water availability and the transition from traditional (or at least, traditionally “Western”) agricultural and resource extraction lifeways to the tech and the service sectors. I spend a lot of time in my academic life thinking about how utopian (and dystopian) visions have shaped the history of the West. I still see those visions today, whether we’re talking about Arcosanti or expanding residential capacity by 300,000 people in Buckeye or wresting new cities from the desert outside of Anthem.

Last week, the Tucson City Council broke into executive session — closing its doors to the public for a meeting with the city’s lawyers — to discuss the possible acquisition of renewable water resources from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

The city has stayed mum on the specific nature of this acquisition, outside of publishing a short memo on the nature of the executive session. Tucson Agenda reporter Joe Ferguson and I have both asked the city about the nature of the discussion. So far, the city hasn’t been willing to explain, and doesn’t have to under the law. (The minutes from these executive meetings are also shielded.)

But there are only so many auctions of federal water resources in a given management area at a given time. And after a little internet sleuthing, we’ve been able to come up with a decent guess.

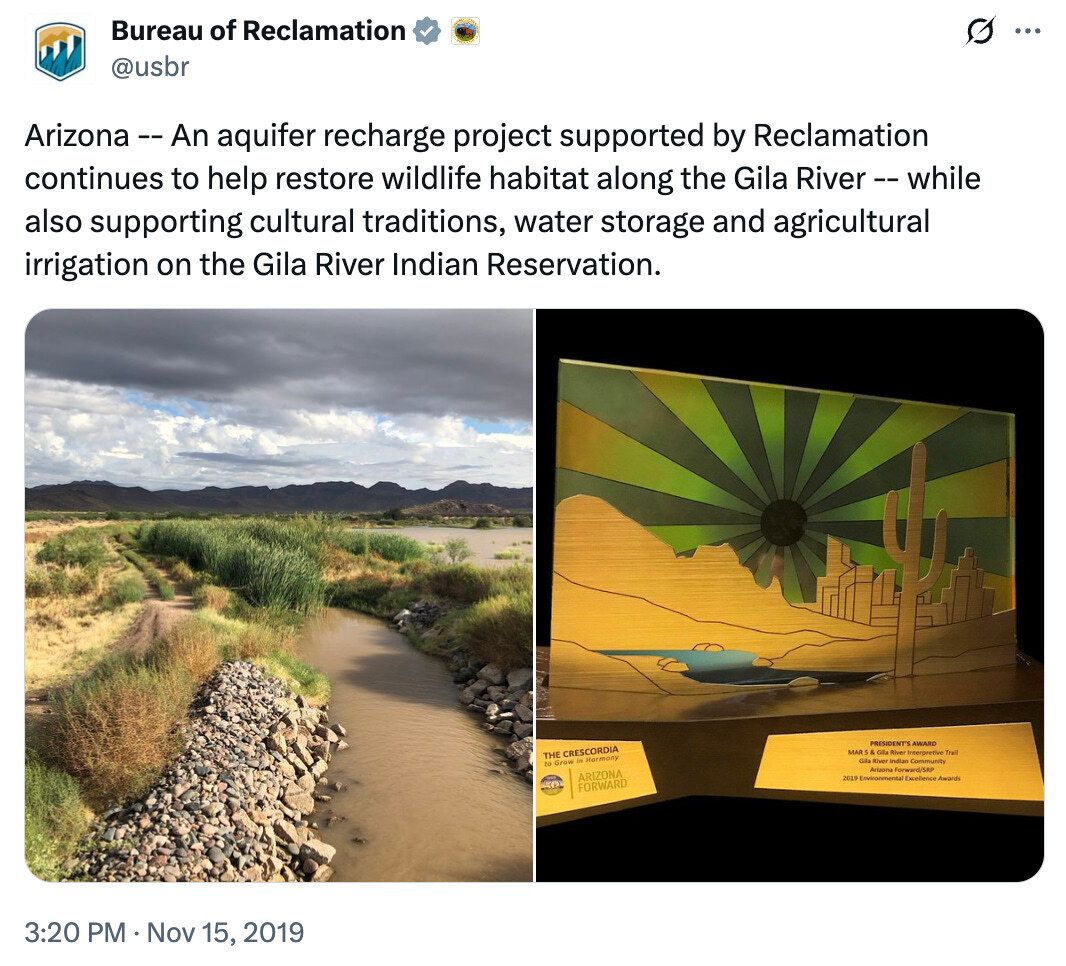

According to the website of the Bureau of Reclamation Phoenix office, the feds are looking to sell up to 30,000 acre-feet of long-term storage credits, which are generated through the storage and recharge of treated groundwater into an aquifer, within the Tucson Active Management Area.

The offer window closed June 9. Representatives from the bureau did not return requests for comment.

Long-term storage credits are one of a number of ways that water can be collected and standardized into a unit of sale.

They first became a thing under Arizona’s 1980 Groundwater Management Act, which, as the name would suggest, established a regulatory scheme to prevent overdrawing of groundwater resources.

A person, company or government that holds water rights can generate credits by storing their water in either an underground storage facility or groundwater savings facility. The distinction between the two is of secondary importance here – the basic idea is this: Water that is stored eventually recharges the aquifer, and, after a year, the water owner can collect their storage credits.

Those storage credits give the owner a right to recover that water for other uses, like providing water to new housing developments. (Though when it comes to buying water credits for housing, we’re often talking about using the credits to demonstrate the presence of a water supply to satisfy the Groundwater Management Act’s requirement that developments in AMAs show they have a 100-year supply of water, rather than actually using the water.)

And the credits can be sold to the highest bidder.

In this case, the Bureau of Reclamation generated storage credits by recharging treated effluent to the Lower Santa Cruz River Managed Underground Storage Project.

Recharging is more or less what it sounds like: “Reclaimed water soaks into the aquifer, it mills around down there, and you get a credit,” Kathryn Sorensen, director of research for the Kyl Center for Water Policy and former director of Phoenix Water Services, explained. “That credit becomes a right to pump a well.”

So what would a municipality want with these credits? In plain language, they want water for growth.

The credits are a way to ensure a stable water supply and the feasibility of development in times of both feast and famine. In many cases, they allow a city or developer to meet legal requirements for water availability.

In order to subdivide land in an AMA into six or more parcels with for-sale homes, a city, developer or water supplier must demonstrate 100 years of continuous water availability. Long-term storage credits are one way to demonstrate that supply.

The credits can also be used to fulfill treaty obligations, recharge obligations and other legal agreements that require someone somewhere to give (or hold) water to/for someone else.

In Tucson’s case, though, it’s unclear that the city would use the credits to demonstrate continuous availability. That’s because under state law, long-term storage credits generated by recharging treated effluent can’t always be used to demonstrate an assured water supply.

Confounding!

But luckily, we have a fairly recent example of an LTSC transaction also dealing with treated effluent that illustrates some of the other reasons for purchasing these storage credits.

In this case, Reclamation sought to sell 60,000 acre feet of LTSCs generated through the storage of effluent in the Santa Cruz storage facilities.

The Central Arizona Water Conservation District, which operates the Central Arizona Project, agreed to purchase the credits at $180 per acre-foot. According to CAWCD meeting minutes from the time, the district needed the credits to meet its obligation to replenish groundwater in the active management area drawn by its members above an allowable amount.

This again illustrates that the credits are less about buying and selling water as it physically exists and more about buying and selling a representation of water availability.

On the other end of the equation, the proceeds from the sale went to a federal account used to fund the development and maintenance of water resources on the lower Colorado.

In other words, we don’t quite know how Tucson might want to use these credits — if indeed this is the potential transaction the council met about last week.

But we have a good sense of how they are generated, sold, and how they can be used. And with the bidding period

Stay tuned for more specifics.

Arizona is growing — and our highways, hospitals, schools, water and transit systems are growing along with us.

Unfortunately, too often, there simply isn’t enough oversight and accountability for these big, taxpayer-funded infrastructure projects.

We can’t afford to have these essential public projects done badly, with unskilled workers in unsafe conditions, leading to costly repairs and rebuilding within just a few years.

Lack of public oversight causes Arizona’s skilled workers to seek work in other states, like Nevada, that ensure fair pay and safer working conditions — meaning Arizona faces a shortage of the skilled workers we need to build our most important projects.

It's time to stand up for Arizona infrastructure and working families.

Build it Once, Do it Right.

Thanks to today’s sponsor, RiseAZ! If you’d like to sponsor an edition of the Agenda, get in touch.

News from the Rockies: The law school at the University of Colorado-Boulder held its annual conference on the law of the Colorado River last week, and while the Agenda couldn’t make it, the majority of water managers representing states on the river didn’t show either. But the Republic’s Austin Corona was there to report what other experts and policymakers had to say about the state of river negotiations.

"We've heard about the stages of grief ... about denial and anger and the need to be at bargaining," said Chuck Cullom, executive director of the Upper Colorado River Commission. "Well, I believe the basin states are there."

Spring has sprung into summer: Spring runoff for most streams in the West has peaked, according to the Land Desk’s Jonathan P. Thompson, who analyzed data from U.S. Geological Survey gauges. With runoff having hit its peak, we can see just how dry the West is this summer. It’s not looking good, Thompson reports.

“What a difference a year can make,” Thompson wrote. “Last year at this time, the West seemed to be on its way to being drought-free, with the exception of New Mexico. Now? Not so much. It’s looking downright grim for New Mexico, Arizona, and southern Nevada, even though the Las Vegas area received a healthy dose of rain in May.”

There goes the neighborhood: Verde Village is figuring out what to do with a privately owned pond — a landmark amenity in the community, according to the Verde Independent — that the village will lose rights to by 2028 because of its non-agricultural use.

“The Ditch Association informed the VVCC in June 2022 and formalized it in January 2023 that it would no longer supply water for non-agricultural uses, effective three years from the notice date,” per the Independent. “At the VVCC’s request, a three-year extension was granted in January 2024, setting the final deadline for water cessation in 2028.”

Está seco en Sonora: It’s important to remember that aquifers don’t care where we build a border wall. Each of the northern Mexican state of Sonora’s 72 municipalities is experiencing “extreme or exceptional drought,” according to KJZZ’s Nina Kravinsky’s report on Mexican government data.

Weather report: Monsoon season officially begins on June 15. So, when can we expect some moisture? Probably not until late July, which really marks the practical beginning of monsoon season for most Arizonans. But it may be a little wetter than usual, the Republic's Hayleigh Evans reports.

“Odds are slightly tilted in favor of above-normal precipitation during this monsoon,” said Mark O’Malley, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Phoenix. “Phoenix has a 40% chance of above-normal precipitation in the monsoon.”

Water prepping: 25.7% of water utilities have fully or partially implemented climate adaptation plans, according to the American Water Works Association’s 2025 State of the Water Industry report.