For years, the seven states of the Colorado River Basin have been trying and failing to negotiate a plan for sharing the river’s water and managing its reservoirs when current agreements expire later this year.

And last week, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation released a long-awaited document that demonstrates the potential price of this failure: heightened risk for a systemwide crash, deadpool at Lake Powell and Lake Mead, costly litigation and more.

The document, technically a draft environmental impact statement for future operation of the federally owned reservoirs at Lake Powell and Lake Mead, lays out five plans for management of the river. The gist? In each scenario, the lower basin states of California, Nevada and Arizona — particularly Arizona, which has some of the lowest priority water rights in the basin — would bear the brunt of cuts to Colorado River allocations. And in some scenarios, even aggressive cuts may not be enough to stabilize the Colorado.

“When they evaluated the different hydrologies that were possible, the one that they defined as critically dry — which actually is not far fetched — there's not a single alternative that they've identified that can save the system in every instance,” Cynthia Campbell, a water policy researcher with Arizona State University, told us. “That’s just flat out sobering.”

None of these plans will necessarily be implemented in their current form — especially if the seven states reach a deal in time to implement a new framework ahead of the 2027 water year that begins in October. But the Lower Basin states have been at longstanding loggerheads with their Upper Basin counterparts in Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah, making federal action on the basin look increasingly likely.

The draft EIS, required under the National Environmental Policy Act, lays the groundwork for such action.

“The Department of the Interior is moving forward with this process to ensure environmental compliance is in place so operations can continue without interruption when the current guidelines expire,” Andrea Travnicek, the department’s assistant secretary for water and science, said in a statement to the press last week. “The river and the 40 million people who depend on it cannot wait. In the face of an ongoing severe drought, inaction is not an option.”

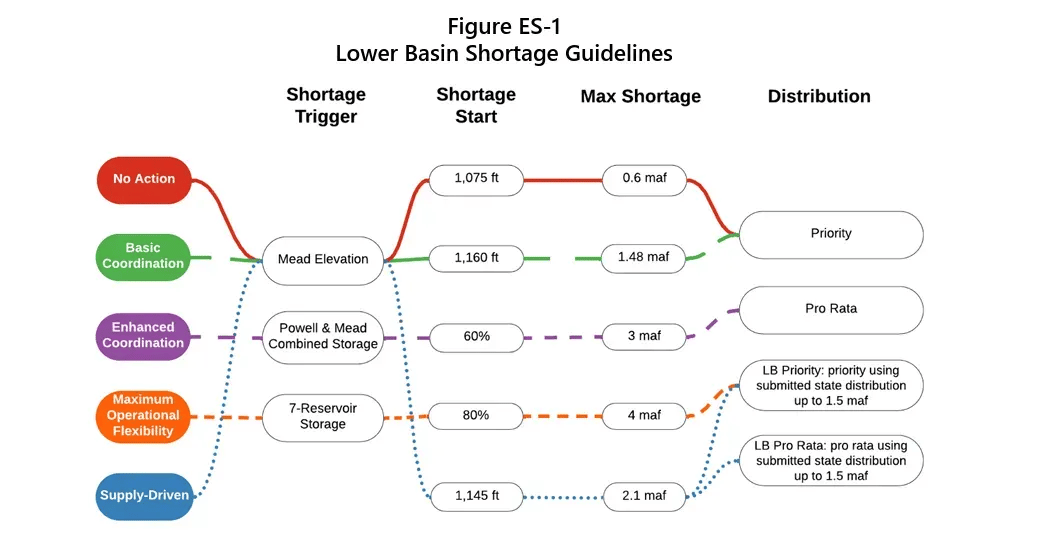

The document includes five scenarios for managing the river.

One, a “no action” option, is required to be described under federal law. The others are based on input from the basin states, many of the 30 federally recognized Native American tribes on the river, environmental groups and other users — though none exactly reflects what the parties have proposed previously. Some plans require cuts according to priority, others according to proportional use. Some would require authority that the federal government says it may not have under existing law. Some would likely require states to waive certain rights and obligations in the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which, among other stipulations, requires that the Upper Basin allows an average of 75 million acre feet of water to make it to the Lower Basin over a 10-year period — something that may be all but impossible under several of the scenarios, a likely trigger for litigation unless the Lower Basin states agree to stand down.

All of the options ask more from the Lower Basin — which, with its large population and economic base, has fully developed and at times exceeded its allocation of Colorado River water — than the Upper Basin, which has yet to grow into its 7.5 million acre feet annual allocation.

That’s been a major issue for Tom Buschatzke, the director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources and the state’s lead negotiator in Colorado talks. The Lower Basin states have put 1.5 million acre feet in annual cuts on the table, but have maintained that the Upper Basin would need to commit to mandatory conservation efforts above that level to save the river.

Even dramatic cuts to Lower Basin allocations — cuts that could kneecap the Central Arizona Project that ferries Colorado water to Phoenix and Tucson — may not be enough to stabilize the river without some contributions from upriver.

For context, current agreements allocate about 18 million acre feet of river water each year, but historical data shows that the average annual flow of the river over the last 500 years is closer to 13.5 million acre feet. That means more than 4 million acre feet in annual reductions may be necessary to stabilize one of the West’s most crucial natural resources — not to mention the source of sacred meaning (and potential revenue) for tribes in the basin, habitat for endemic plant and animal life and outdoor recreation. And without dramatic cuts or a surprisingly wet winter, we’re also fast approaching deadpool levels at the two reservoirs, the point at which hydropower generation becomes impossible and the delivery of water through the dams becomes an infrastructural challenge.

None of the options in the document are acceptable for Buschatzke, he said in an interview this week.

"So I believe that the alternatives collectively, or each alternative individually, put huge amounts of reduction and pain on the Lower Basin and the state of Arizona," he said.

He added that he could not in good faith bring a plan to the Arizona Legislature that calls for the kind of reductions the state would face under the alternatives or that would result in Arizona waiving its right to sue under the compact without significant concessions from the Upper Basin.

What’s in the document?

The draft EIS is a more-than-1,000 page document full of technical notes, tables and appendices that may confound even the most seasoned water hound. We’ll link to it here for the brave.

But it essentially outlines five potential scenarios that the feds could impose if the states don’t reach their own agreement.

The feds say that these five scenarios are designed as “interim” plans that would last for about 20 years, though they say they’d be open to a shorter-term plan if the states can agree on a larger framework. That meshes with what Gene Shawcroft, Utah's Colorado River Commissioner, said following meetings in Salt Lake City this week: A five-year plan may be more feasible than a long-term agreement.

Buschatzke said this week that he would prefer a deal with a longer lifespan, but that some kind of hybrid might be possible — a plan with a five-year deal and a conceptual framework for operations after that point that would allow flexibility to adapt to changing conditions.

"It all comes down to your risk tolerance, and one of the key elements to determine risk tolerance is how much water flows from Lake Powell to Lake Mead, at least for us in the Lower Basin," he said. "Once we start to nail that down, I can further answer the question about five years, six years, 10 years, whatever."

1. The feds do nothing

The first option, the “no action” scenario, is largely perfunctory — the document must include such a scenario under federal law, though it almost certainly would not be adopted.

In this case, river operations would be guided by agreements from the 1970s, and the feds would make annual determinations of river allocations.

2. If states do nothing

The second, dubbed the “basic coordination” alternative, is the only new option that wouldn’t require additional agreement among the states, making it a likely — if short-term — option if the states do nothing.

It lays out annual cuts of up to about 1.5 million acre feet in the Lower Basin, depending on the hydrology of the river that year, with almost 80% of those cuts coming from Arizona.

This could be devastating for the state, and perhaps more importantly, still not be enough to save the river in all but the most optimistic hydrological projections.

“Reclamation acknowledges that the operations under this alternative may not provide adequate protection of critical infrastructure or the system and may be viable only in the short term given current reservoir conditions,” the document reads.

3. Protect the power

A third option, dubbed “enhanced coordination,” is based on concepts put forth by a group of basin tribes, federal agencies and other stakeholders.

“This alternative seeks to protect critical infrastructure while benefitting key resources (such as environmental, hydropower, and recreation) through an approach to distributing storage between Lake Powell and Lake Mead that enhances the reservoirs’ abilities to support the Basin,” the document reads.

It would distribute up to 3 million acre feet in cuts to users in the Lower Basin based on proportional use, sidestepping the priority system — meaning that California would take the brunt of the cuts. Releases from Powell downriver would be based on conditions at both Lake Mead and Powell, rather than strictly the Upper Basin's delivery obligation.

The plan also assumes between 200,000 and 350,000 acre feet in annual Upper Basin reductions — though it’s not clear where these cuts would come from or under what authority they’d be enforced or incentivized.

4. Protect the water

A fourth option, the “Maximum Operational Flexibility Alternative,” is based in part on ideas from environmental groups in the basin.

It would allow a wide range of cuts from 1 million acre feet to 4 million acre feet per year, depending on hydrology, storage levels and other factors, with up to 500,000 acre feet coming from the Upper Basin. Cuts of 4 million acre feet a year would represent more than four times CAP's entire annual delivery in recent years, for context. Like the "enhanced coordination" plan, this proposal would allow smaller releases from Powell than what the Lower Basin is entitled to under the compact. It also describes a conservation pool of up to 8 million acre feet that could be used to stabilize the reservoirs at Mead and Powell.

In terms of maintaining river levels and protecting critical infrastructure, this “isn’t a bad alternative, but it’s a painful alternative,” Campbell said. But 4 million acre feet in cuts “might be what we need to stabilize the system.”

And even these dramatic cuts may be insufficient in “critically dry” hydrologic futures.

“We've pushed the system so hard and so far down that what it will take to get it to a sustainable level is a pretty dramatic change. It's a pretty dramatic cut in demand. It's potentially a change in the priority system,” Campbell said.

5. The percentage cut

The fifth option is dubbed the “supply driven alternative,” which calls for the Lower Basin to take annual shortages ranging from 1.5 million acre feet to 2 million acre feet per year, with the distribution of cuts based both on priority and proportional use.

Releases from Lake Powell to Lake Mead would be based on a percentage of three-year flows at Lees Ferry, which are meant to represent the natural flow of the river without diversions, rather than historical data.

The Upper Basin states would take up to 200,000 acre feet in annual cuts.

Can they do that?

As we’ve explained throughout our reporting on Colorado River talks, the federal government has a clear authority to dictate Colorado River cuts and deliveries in the Lower Basin.

In the Upper Basin, that authority isn’t as certain. And that makes the prospect of mandatory cuts to Upper Basin users a little unclear, although Lower Basin states contend that the federal government’s obligation to protect its infrastructure and ensure compact compliance means it has the authority to compel action in the Upper Basin.

This uncertainty is reflected throughout the document, which includes specific, high-volume cuts for the Lower Basin but only the framework for possible, low-volume cuts from the Upper Basin. When it lays out Upper Basin cuts — say, between 200,000 and 350,000 acre feet — the document is clear that it makes no assumptions about where those cuts would come from and gives little other detail.

“The full extent of Reclamation’s operational authority has not been tested to date — either operationally or through legislative or judicial review,” the document says.

The document does say that the federal government maintains its authority to pull water from the Upper Basin — the Colorado River Storage Project, or CRSP, reservoirs — to protect hydropower generation and other needs at Glen Canyon Dam.

But even that would be legally contentious in the Upper Basin. And beyond that, the feds say they would likely need additional authority — presumably from Congress, though potentially in the form of an agreement from the states — to prescribe Upper Basin cuts.

From Arizona’s perspective, this is certainly better than the feds flat out saying they don’t have the authority to make Upper Basin cuts. But it doesn’t mean much when basically any path forward could trigger litigation.

“It's our position that they have the authority to move water to protect infrastructure, and to move water from (the CRSP reservoirs) through Lake Powell to Lake Mead to meet compact obligations," Buschatzke said. "We believe that that's clearly enunciated in the 1956 Colorado Storage Project Act that authorized the building of those reservoirs. "

Part of the purpose of negotiations between the states is to get them to agree to stand down from the threat of lawsuits — but that hasn’t happened. And any lawsuit would take up time that the river realistically doesn’t have.

And while some of these proposed alternatives would be better or worse for Arizona, all of them would be painful.

But the worst scenario for Arizona, Campbell said, is the worst scenario for the rest of the basin — that no matter what action the feds or states take, the river system crashes.

That could mean a cascading series of consequences: first goes power generation, then water deliveries through the dam turbines, which could threaten the physical infrastructure of the dams. Farmers would end their seasons early. Cities like Phoenix would have to tap various alternative water supplies. And everybody would be at each other’s throats — even more so than at the present time.

“I don't think that there's really been an adequate consideration of what happens if that happens, right?” Campbell said. “I don't know how you put Humpty Dumpty back together again if you crash the system.”

Again, none of these scenarios may come to pass, especially if the states reach agreement. But the hydrology gives little reason for optimism, Campbell said.

In one sense, that’s part of the purpose of this document — to present options so odious to both sides that they will come together at the bargaining table before a looming Feb. 14 deadline to come up with at least a sketch of a plan.

But it’s the Lower Basin that stands to lose the most in these scenarios, so it’s hard to say how the EIS will impact negotiations. And the EIS itself is a draft at this stage, open to comment by members of the public and stakeholders through early March. Reclamation is hosting two virtual public meetings to hear comments, one on Jan. 29 and the other on Feb. 10.

The governors and negotiators of the basin have also been summoned to Washington, D.C. for a summit with Interior Secretary Doug Burgum late next week, a last-ditch attempt to find consensus.

"I do think we are at such a level of stalemate that I'm hopeful that the governors sitting in a room might be willing to, in real time discussions, agree to some things that might break loose some of the things that need to be addressed, in a way that we who are the governor's representatives, can't really do," Buschatzke said.

He said he's not sure which governors will attend, but that he's been assured enough are coming to keep the meeting on the schedule.

"I got my plane ticket, I got my hotel, and I'm on my way," he said.