In August, federal officials said Arizona, Nevada and Mexico would each see continued cuts to Colorado River allocations in 2026.

Those cuts highlight a bigger problem.

In 2026, the agreement that lays out the tiered cuts — the 2019 Drought Contingency Plan — expires, as do a series of other federal rules that were patched onto the existing river regulatory framework as drought in the southwest worsened.

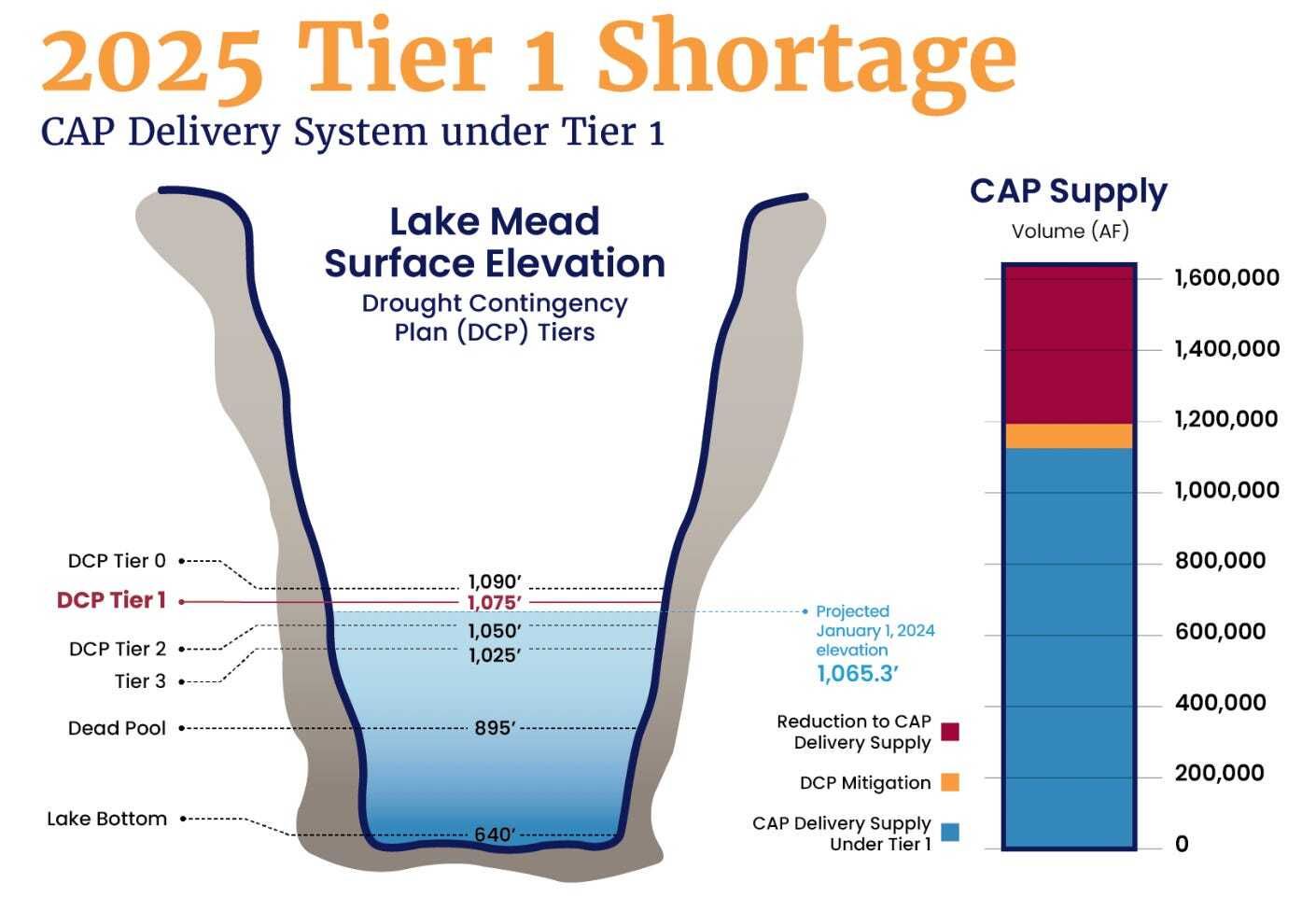

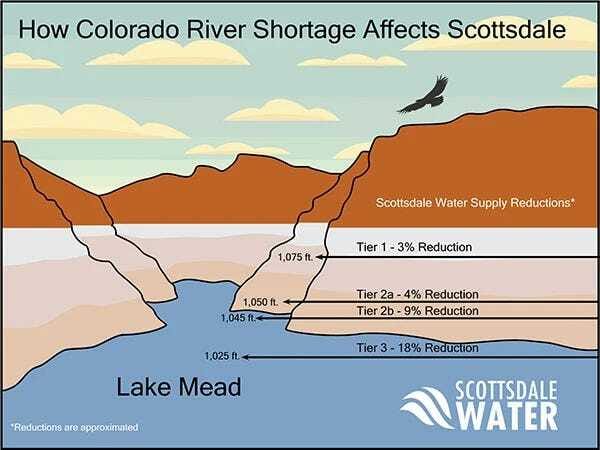

The cuts mean a 512,000 acre-foot reduction to Arizona’s Colorado River supply, which works out to 30% of the Central Arizona Project’s regular supply and 18% of the state’s overall share of the Colorado River, per CAP.

CAP users bear almost all of the cuts, and agricultural users will feel it most deeply, especially in Pinal County, where farmers have low-priority water rights.

The Tier One cuts, based on projections from Lake Mead and Lake Powell, were hardly a surprise. Arizona was already in a Tier One scenario, and in fact had faced deeper, Tier 2 cuts in the past.

And the winter runoff that feeds the reservoirs was pitiful this year — mountains in the Rockies held less than half of their average snowpack, a hydrologic reality reflected in diminished inflow to Lake Powell.

Negotiators from the basin states have been working to come up with a new plan, but have repeatedly found themselves at loggerheads. If they don’t come up with a draft plan by mid-November and finalize it by the middle of next year, we don’t really know what will happen. But it will likely be painful.

The feds, for one, have said they would step in, but that raises some questions about their legal authority. Doing nothing means reverting to rules from the 1970s, the Long-Range Operating Criteria, which reflect a completely different hydrological reality — and one might argue the criteria were overoptimistic even then.

“If there is no federal action, the risk is of getting no hydropower and deadpool,” meaning reservoirs get so low water can’t flow past dam outlets, Sarah Porter, the director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University, told us.

For a moment, it looked like negotiators were making progress.

Arizona Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke unveiled a “supply-driven” plan in June that would allocate water to the lower basin states based on three-year average flow measurements at Lee’s Ferry, rather than based on the 7.5 million acre-feet per year allocations that each basin receives currently.

“What that would do, that I think is the big innovation, is instead of continuing to struggle with the fact that this river doesn’t produce 15 million acre feet of water, let’s look at the flows in the river, and look at what nature is really giving us,” Porter explained.

The states seemed to agree on the plan’s broad strokes, at least philosophically. But a recent E&E News report suggests that as negotiations got more specific, they ground to a halt on familiar lines: how much water should each state get and how cuts should be shared.

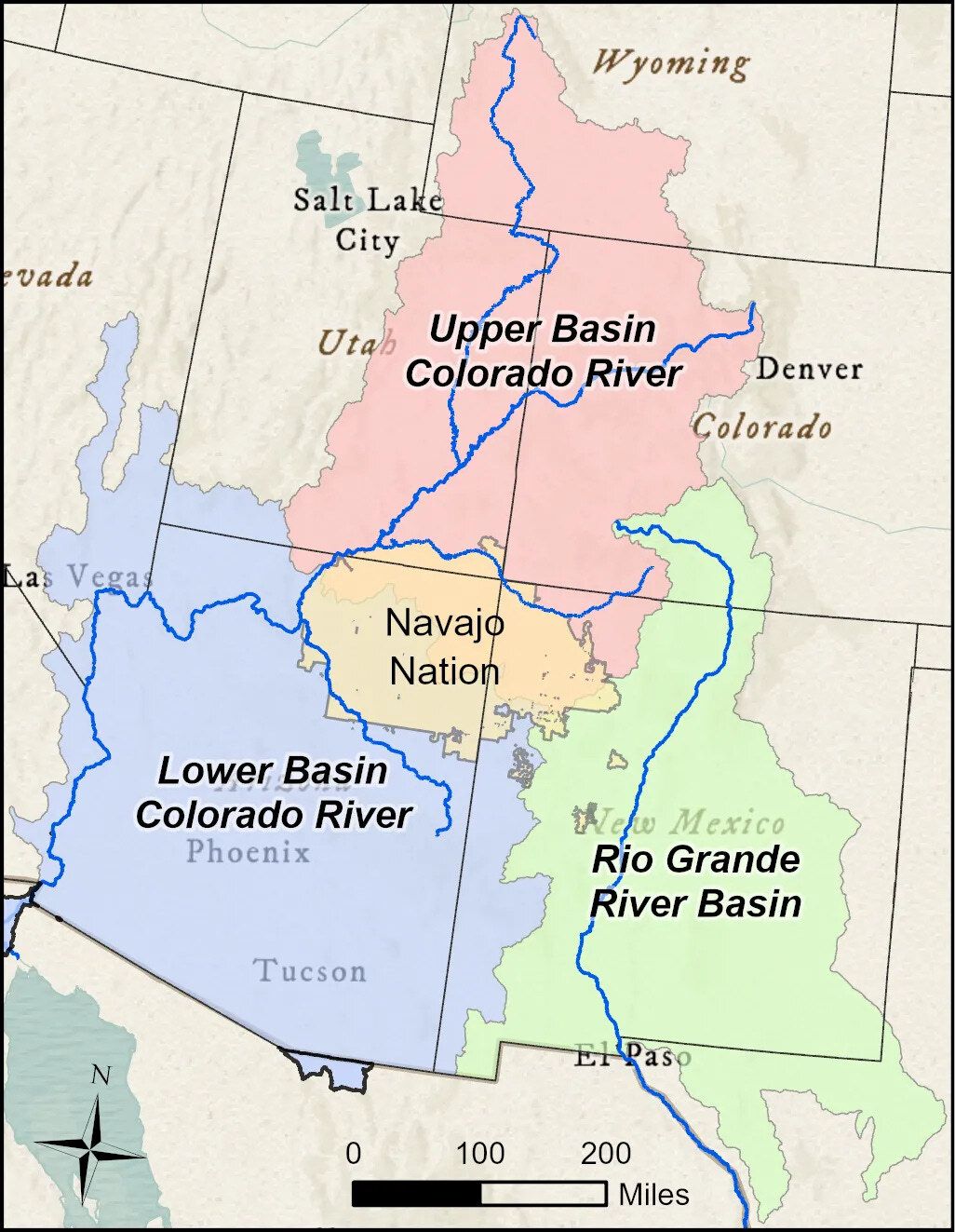

“Fundamentally, one of the biggest sources of disagreement between the upper and lower basin is the difference of view about whether the upper basin has any obligation for how much the lower basin gets,” Porter said.

That meshes with what Buschatzke has said publicly about negotiations in recent months: “The path to success seems tenuous at this point,” he told the Denver Post at the end of August.

In the E&E piece, CAP general manager Brenda Burman put the situation in starker terms.

“What we have seen from our upper basin, upriver neighbors is an absolute unwillingness to guarantee any sort of water reaching the lower basin whatsoever,” she said.

While the upper basin states have the direct line to the (albeit diminishing) snowmelt that feeds the river and thus the reservoirs, it’s the lower basin states that host bigger populations, higher levels of agricultural production and have already borne the brunt of Colorado River cuts.

These competing interests have manifested in differing interpretations of the so-called non-depletion requirements in the 1922 Colorado River Compact. The compact says that the upper basin states “will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75,000,000 acre-feet for any period of ten consecutive years.”

To the lower basin states, that means the upper basin has an obligation to deliver a certain amount of water downstream. To the upper states, the compact provision simply means they can’t use above a certain amount of water if it seems 75 million acre feet won’t make it downriver. Meanwhile, upper basin states argue that they effectively face cuts in the form of diminished snowmelt and other climatic changes, and it's the lower basin states that need to rein in unsustainable consumption.

“Arizona’s new proposal of a supply-driven approach offers hope, but the devil’s in the details. Critical components of that approach have not been ironed out – for instance, the percentage of the river’s flows that would be available to Arizona, California and Nevada,” Porter wrote in a recent paper.

No matter what, Arizona is likely to face continued reductions to its Colorado River water supply. Some cities have already adapted to new realities, pursuing alternative water sources and reducing consumer demand.

But farmers and tribes have fewer backups, Porter said. If the states reach a lasting impasse, we don’t really know what federal action could look like. Litigation — between the states, or from states challenging the government’s authority to make unilateral plans — seems all but guaranteed.

Either way, the uncertainty is bad for everyone.

“Farmers tend to finance what they do, to grow crops that are financed, to develop multiyear crop plans — they need to review with a funder, a lender,” Porter said. “It’s the same for everyone who uses Colorado River water. There’s a huge cost to the uncertainty.”

Buschatzke, meanwhile, is using startlingly warlike language to describe the situation from his point of view. He recently took to the op-ed pages of the Denver Post — behind enemy lines, so to speak — to rally Coloradans and other upper basin dwellers to convince their officials to see things his way.

Failure by the upper basin states to agree to reduce their usage, forcing all the cuts to the lower basin, “could bring Arizona’s people to their knees,” he said.

“I implore the citizens of the Colorado River Basin to rise up and demand that the negotiators for Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico partner with Arizona, California, and Nevada and put mandatory, certain, and verifiable water-use reductions on the table for their four states,” he wrote. “That is the only outcome that can result in a seven-state agreement. In the alternative, the path we are on can be best captured by a quote from William Shakespeare's ‘Julius Ceasar,’ ‘Cry Havoc and let slip the dogs of war.’”

Deadlines in the Colorado River talks are looming large across the state and region.

At the municipal level, more than 20 Arizona mayors — representing communities with some very different needs and desires and approaches to water management, from Phoenix’s Kate Gallego to Queen Creek’s Julia Wheatley — have banded together to form the Coalition for Protecting Arizona’s Lifeline, “a nonpartisan alliance committed to collaborating and advocating for Arizona’s allocation of Colorado River water,” per a CAP press release.

Collectively, the mayors expressed a familiar sentiment in the lower basin states: We’ve taken serious cuts in the past, and are willing to be responsible in the future, but Arizona needs Colorado River water.

“Any dramatic reduction or reallocation of Colorado River water that CAP delivers to its users would have significant negative implications for our total quality of life, economy and the security of our country,” Tucson Mayor Regina Romero said in a statement. “We want to make it clear through this coalition and our collaboration that water security is not a partisan issue. It is a shared Arizona priority that transcends political lines and regional divisions.”

In Indian Country, meanwhile, officials from the Navajo, Hopi and San Juan Southern Paiute tribes met with representatives from the Department of Interior and the Bureau of Reclamation following the reintroduction of the Northeastern Arizona Indian Water Rights Settlement Act, per the Arizona Republic’s Arlyssa Becenti. The settlement, which requires Congressional approval, would be the largest tribal water rights settlement in U.S. history.

Perhaps its most important provision is providing $5 billion for water pipelines and storage facilities that will bring clean drinking water to tribal land that lacked it previously. Tribal water rights account for a quarter of Colorado River allocations, with the Navajo holding the biggest obligation. The settlement would also allow Navajo and Hopi water rights holders to lease some water off the reservation.

“For generations, our Navajo people in many communities have waited for access to clean, reliable water,” Navajo Speaker Crystalyne Curley told Becenti. “Meeting with the Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Reclamation is an important step in ensuring that the resources, technical expertise, and federal commitments are in place to make this settlement a reality.”

The progression of the settlement will certainly be made easier by broader agreement about the disposition of Colorado River water between the basin states, but that hasn’t happened.

“This is something that needs to move forward,” Bidtah N. Becker, chief legal counsel for the Navajo Nation, told the St. George News in July. “The reason it hasn’t moved forward is because we are situated in the heart of the Colorado River Basin.”

Fondomonte makes its case Fondomonte, the Saudi-owned subsidiary pumping groundwater in La Paz County to grow alfalfa for cattle in Saudi Arabia, is asking a state judge to throw out Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes’ lawsuit against the operation. Lawyers for the company argue that Mayes’ efforts to have the operation declared a nuisance for its “excessive” groundwater pumping — an untested strategy partly designed as a message to legislators who have failed to pass comprehensive groundwater management bills — exceed the purview of her office. Fondamonte is also asking the judge to pause discovery in the case pending his decision on the company’s motion to dismiss Mayes’ complaint.

“Because the Attorney General lacks authority to regulate groundwater use, her Complaint exceeds the bounds of her constitutional role and improperly invites the Court to wade into a political question that intrudes on the Legislature’s exclusive policymaking function,” lawyers for Fondamonte wrote in a filing to Arizona Superior Court Judge Scott Minder last week.

Game over: An Arizona wildlife management official told the state Game and Fish Commission last week that drought is causing decreased populations of quail, and encouraged commission members to adopt tighter restrictions on the hunting of game birds, per the Arizona Republic’s Brandon Loomis.

“This is not the year to be quail hunting in Arizona,” small game program manager Larisa Harding told commissioners.

Dry times on the San Pedro: One of the groundwater monitoring wells in the San Pedro Conservation Area has run dry, according to the Center for Biological Diversity, which is engaged in litigation to protect the San Pedro, the last free-flowing river in the Southwest, from excessive groundwater pumping.

“What more proof do our leaders need that the San Pedro is being sucked dry?” Robin Silver, a co-founder of the Center for Biological Diversity, said in a press release. “Years of inaction and relentless over-pumping in Fort Huachuca and Sierra Vista are pushing the river and the extraordinary plants and animals it sustains to the brink. Arizona and the federal government must act urgently and decisively to save this ecological treasure from extinction.”

A day at the races: An organization in the north Valley that rescues and rehabilitates aging and injured race horses has seen its well run dry, illustrating the challenges facing far-flung Valley exurbs that are dependent on groundwater. The organization is trying to raise $45,000 to dig a new well, per ABC15.

The floating dead: Officials identified the body of a man missing since 2023 in Lake Powell in part thanks to fluctuating water levels, reports the Republic’s Austin Corona. This might sound familiar — for several years now, recreationalists and law enforcement on the two major Colorado River reservoirs in Arizona have encountered long-dead corpses revealed by declining water levels, particularly those who appear to have been sent to their watery fates in Lake Mead in Casino-esque Las Vegas gangland killings. What makes this particular corpse interesting, though, is how new it is. The vehicle of Dennis Keith Dillinger went into the water at a time when the water levels in Lake Powell were 24 feet above where they were when his vehicle was discovered, Corona reports.

“The discovery also shows how a single strong runoff year, 2023, postponed serious water shortages on the Colorado River, and how, two years later, as the water recedes again, those shortages loom on the horizon,” Corona wrote.

It isn’t necessarily funny, but it sure is illustrative, in a sort of funny way: The tiny unincorporated La Paz County community of Wenden is sinking several inches a year because of groundwater withdrawals from big industrial agricultural operations in southwestern Arizona.

"Even customers this last year have noticed," a local business owner told Fox 10. "They’re like, 'whoa' — they feel like they’re sliding in.”

At a point a mile north of Wenden, academics have measured the subsidence — basically, when the land sinks because water or other materials underneath it are removed — at more than six feet since 1991, and the sinking is continuing as the aquifers run dry and wells are drilled ever deeper.