Republican Rep. David Marshall submitted testimony to the Arizona Corporation Commission recently opposing a water rate hike for communities that would subsidize the cost of a fancy, and unnecessary, underground water storage tank for their neighbors in Sedona.

Many would agree with Marshall that it's “a matter of fairness and affordability” – but it’s more than that. If the ACC approves the requested rate hike, it sets a dangerous precedent that can escalate.

Today, we’ll use game shows and psychological research to understand, once again, how complex the world of water can be.

Speaking of fairness and affordability, the Water Agenda is free! But it’s also pretty affordable to support our work.

A split or a steal?

Maybe you’ve seen a clip of the British game show “Golden Balls.” It’s the one where two contestants must secretly choose whether to split or steal a jackpot. If both choose “split,” they share the cash. But if one chooses “steal,” they take it all.

And if both choose to steal? Then, both lose everything.

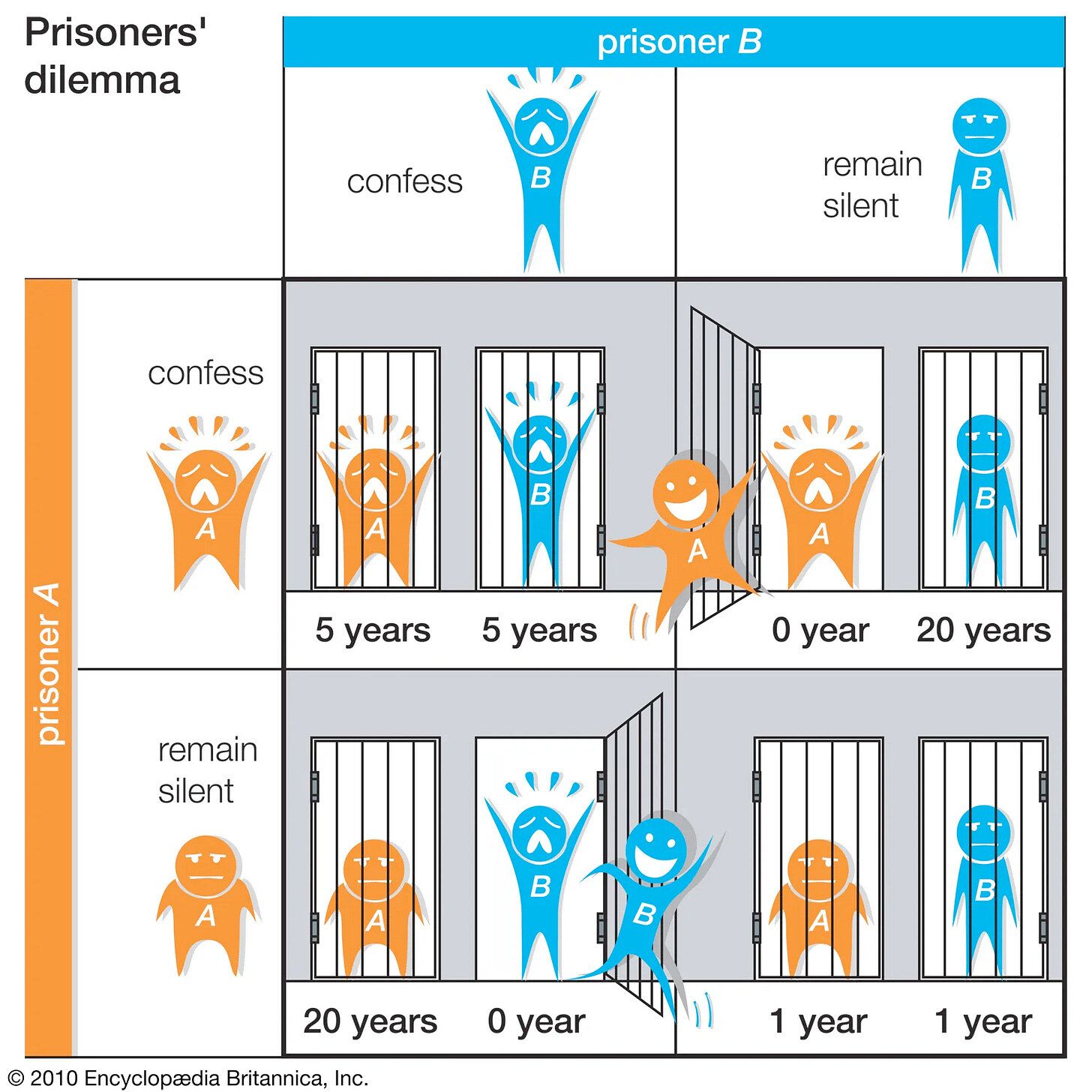

It’s a televised version of the famous “Prisoner’s Dilemma” scenario — if two suspected partners-in-crime both remain silent under interrogation, they can both avoid jail time. If one rats the other out, they get a light sentence, but the other gets a heavy sentence. If they both rat each other out, they both get moderate sentences.

Game theorists call this kind of situation a "multipolar trap," where distrust pushes everyone toward selfish choices — even if cooperation would be the most beneficial option.

In rural Arizona, for instance, the multipolar trap of groundwater is called the “Race to the Bottom.” Without shared limitations on pumping, farmers know that if they don’t pump the aquifer dry, someone else will. So there’s no incentive to self-limit, and water levels keep dropping and wells keep going dry. (Which, btw, is why there’s no substance to certain politicians’ and lobbyists’ claims that a “voluntary” system for pumping reductions can solve groundwater overdrafts — no one’s going to volunteer.)

A money vortex

Which brings us to Sedona, the scenic, Airbnb-packed town famous for its vortexes and views of red-rock cliffs. Sedona recently asked the Arizona Water Company (AWC) to build a new underground water storage tank with above-ground facilities disguised as a fancy home. The idea is to protect their tourism-generating views and property values.

But burying a massive tank underground costs millions more than a typical above-ground tank. Throw in a pumping station because there’s no gravity pressure, and a fancy decoy WaterBnB to hide the pumps, and the bill comes to roughly $20 million.

Ok — Sedona is going to do Sedona. But Sedona wants nearby towns serviced by AWC to help cover their project costs via a distributed water rate increase, even though those distant towns gain no benefit. Sedona argues that the cost-sharing aligns with recent trends. AWC has been consolidating rates region-wide, which helps prevent rates from spiking when any community’s water system needs essential repairs or upgrades.

"Deconsolidation for purposes of the East Sedona water tank would be a step backward," Sedona City Manager Anette Spickard wrote to regulators.

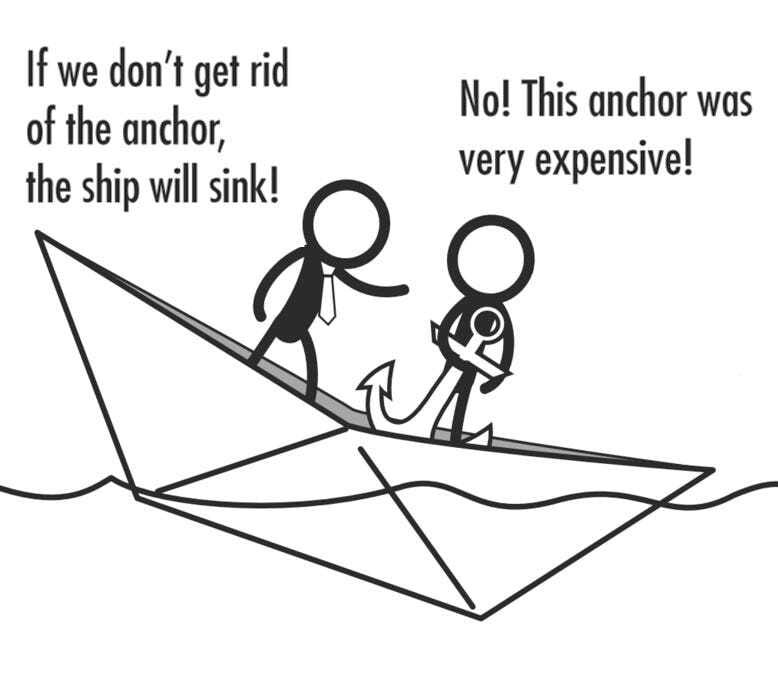

But here’s the rub: Sedona’s underground tank isn’t a necessity — it’s a luxury. In fact, it’s “one of the most expensive” projects AWC has developed. If the Arizona Corporation Commission allows Sedona to shift the cost to other communities, it sets a dangerous precedent that will put ratepayers in a race to the bottom of their bank accounts — they’ll be creating a multipolar trap.

‘Till water bills do us part

Other towns might have no need for luxury water system accoutrements. But when they start getting billed for Sedona’s add-ons, are they going to cut their losses, or start making similar luxury demands at everyone’s expense? Research says they’ll bite back.

First, consider the “sunk cost fallacy” — the tendency to think that if you’ve already lost money to something that isn’t working, you might as well invest more until it works. “If our rates are getting hiked, might as well hike them a little more and get something out of it,” thinks the ratepayer.

But it’s not just about avoiding a loss — it’s about our sense of justice.

Behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman’s bestselling book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, provides insights into how we humans would rather take a loss than see someone else unfairly take a win. Research subjects are presented with the “Ultimatum Game” scenario:

Two players are given the chance to split a sum of money, say $10.

Player A proposes how to divide it(e.g. “I’ll take $8, you get $2”).

Player B can accept or reject the offer.

If Player B accepts, both get the proposed amounts.

If Player B rejects, both get nothing.

The economic choice for Player B would be to accept any nonzero offer — even $1 — because $1 is better than $0. But in practice, Player B often rejects offers under 20–30% out of a sense of fairness — and both players get nothing. It’s the Golden Balls game, except you already know the other person chose “steal,” and you’re not going to let them get away with it.

Similarly, once Sedona gets special treatment at the expense of neighboring towns — like Pinetop-Lakeside or Rimrock — those towns will naturally want their own premium upgrades, and for Sedona to pay for them.

And then every other community is increasingly incentivized to seek luxury upgrades, and everyone’s water bills go up.

And who really wins?

While the communities in Arizona Water Company’s “Northern Group” of water users might find themselves stuck in the money pit of a multipolar water trap, AWC walks away with the money bags from all the costly upgrades and add-ons.

The arc of justice: The Northeastern Arizona Indian Water Rights Settlement Act, reintroduced this year in Congress, would resolve historic water disputes on the Colorado Plateau and provide crucial funding for a pipeline to pump Colorado River water to isolated Hopi communities, Christopher Lomahquahu writes in a feature for the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting.

“Turning this vision into reality will take time, though, and the clock is running out,” Lomahquahu writes. “As tribes strive to build a consensus among the seven Colorado River Basin states, a critical step toward finalizing the water settlement, federal delays continue to slow progress. At the same time, growing populations and shrinking Colorado River reserves have intensified pressure on the states to renegotiate how they share the basin, a critical water source for all seven.”

Data center drawdown: Large utilities in the southwestern states of Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah are anticipating a 50% increase in energy demand by 2035, primarily because of large-load commercial customers like data centers, according to a new report from Western Resource Advocates, an environmental group. The report, which analyzed Integrated Resource Plan documents from each state’s utilities, additionally found that data center water consumption under the projections would work out to something like 7 billion gallons a year by 2035.

Not-so wet, hot summer: Water elevation levels at Lake Powell are about 29 feet lower than this time last year, and certain boat launch ramps will begin to close in August, according to an Arizona Daily Sun writeup of a National Park Service announcement.

WIFA still has some juice: The Oro Valley Water Utility will receive $3 million from the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority of Arizona to support a renewable water project in the region called the Northwest Recharge and Recovery Delivery System, per KVOA’s Marissa Orr. WIFA, as KJZZ reported earlier this month, has become something of a budgetary football, facing repeated cuts over the last several legislative sessions. The project comprises new recovery wells and a pipeline that will be used to convey stored Central Arizona Project water to about 115,000 people in northwest Tucson.

Well wars: The U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals last week reversed a lower court ruling that closed a series of private wells along the Gila River, which the Gila River Indian Community argued violated its tribal water rights, per Courthouse News’ Joe Duhownik. The dispute centers on the relationship between the wells — and the groundwater they pull — and the surface water of the river, which is reserved for the tribe. The judge wrote that the remedy of closing the wells is overly broad and sent the case back to the trial court.

Gail force: Regular Water Agenda readers should be well familiar with Hereford Republican Rep. Gail Griffin, whose outsized role in shaping water policy at the Capitol has thrust her into the pages of the Agenda here, there and elsewhere. Those looking for more background should check out a new profile on Griffin from the Associated Press’ Sejal Govindarao. The piece covers some well-tread ground: Griffin, as longtime chair of the House Natural Resources Committee, is able to decide what water bills live and die, often making that determination with the interests of private property owners and big ag in mind. But the AP was also able to grab a rare statement from the infamously taciturn lawmaker. Here’s what she said (admittedly via email):

“As we work with stakeholders, we will continue to support private property rights and individual liberty while ensuring that any legislative solution protects local communities and our natural resource industries, allowing rural Arizona to grow.”

Imagine a faster, safer commute.

Arizona has a five-year plan to fix our roads, so let’s make sure we do it right the first time.

That means using skilled, fairly paid workers, ensuring safety on the job, and providing real oversight to make sure these public projects are actually built to last.

Let’s fix traffic the right way — once and for all.

Learn more at Rise-AZ.org.

We are mourning longtime former Democratic lawmaker and civil rights leader Alfredo Gutierrez, who passed away this week at 79.

While much of the press coverage — understandably — has focused on his advocacy for immigrants and his work to establish Arizona’s Medicaid agency, we’ll also point out that as Senate minority leader, he was instrumental to the passage of the 1980 Groundwater Management Act, a landmark piece of bipartisan legislation still governs groundwater usage today.

Other legislative leaders involved with the deal — which was signed by Gov. Bruce Babbitt — include a number of late titans of Arizona politics, like Stan Turley and Burton Barr.

“It was a different era,” Kathleen Ferris, the executive director of the Arizona Groundwater Study Commission during GMA negotiations, told the Arizona Capitol Times earlier this year. “I just haven’t seen that kind of momentum and that kind of spirit of, ‘we need to get something done and we’re all trying to do something. Not the same thing, but we’re pushing toward the same goal.’”