Today we’re taking a field trip to Where The River Ends.

The Colorado Delta, what’s left of it, is a portrait of what happens when a region’s source of water goes missing.

The Ciénega de Santa Clara is Mexico’s accidental oasis, fed by Arizona.

And the Tijuana Aqueduct delivers snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains all the way to a water-scarce coastal city.

Then we’ll hear about what NGOs, academics, and ex-officials are saying about the post-2026 management of the Colorado River, and why one Arizona senator is pushing a bipartisan bill in Congress to protect water infrastructure from foreign cyberattacks.

A Paradise Lost

A long time ago, at the Mexicali coast, the Sea of Cortez greeted the fresh waters of the Colorado River after their long journey south from the mountains of North America.

The Colorado Delta was roughly 2 million acres of rivers, backwaters, and wetlands. Back in 1922, American ecologist Aldo Leopold described it as “a milk and honey wilderness” of “a hundred green lagoons.”

This paradise in the desert supported giant fish, lush cottonwood-willow galleries, and vast flocks of migratory birds. The indigenous Cucapá — literally the “River People” — relied on seasonal floods for fishing, farming, and ceremony. Today, only fragmented patches remain where fresh water trickles through salt-crusted sands.

Starting with the Hoover Dam in the 1930s, nearly all of the river’s flow was captured upstream for farms and cities. By the 1960s, zero acre‑feet reached the delta’s end, and 90 percent of the wetlands dried into salt flats and dusty plains. Native cottonwood and willow vanished, replaced by invasive saltcedar. Fish populations plunged, and the once‑bustling estuary nursery for corvina and shrimp collapsed.

A turning point came with 2012’s “Minute 319” update to the U.S.-Mexico Water Treaty, an agreement to deliver water for the delta’s environment. In spring 2014, a “pulse flow” of 105,000 acre‑feet simulated a spring flood, sending water across 70 miles of desert and recharging soils. Within months, the 275,000 planted cottonwood and willow seeds were sprouting, and bird counts rose by 20–60%. Follow‑on base flows and targeted plantings by NGOs under Minute 323 (through 2026) promised another 210,000 acre‑feet from the River and 11,000 acre‑feet of treated wetland discharge annually.

For many young locals, the strategic releases of Colorado River water into the area was their first opportunity to see and enjoy fresh water. Older locals thought it was something they’d never see happen again. Environmentalists rejoiced.

But the future of the area is uncertain, with Colorado River water shortages and new agreements being worked out for 2026.

An unexpected oasis

Nestled amid Sonora’s salt‑crusted plains, the Ciénega de Santa Clara is a surprising emerald ribbon in the dried‑out Colorado River Delta. The water that feeds it is an agricultural byproduct from Arizona.

Farms near the border in Yuma have salty soil which saturates the runoff from irrigation. This water was being sent back into the Colorado River near the border, and Mexico complained of the high salinity in the water they were receiving downstream.

This prompted the 1973 “Permanent and Definitive Solution” salinity treaty. To comply, the U.S. built the Main Outlet Drain Extension (MODE) canal to divert roughly 100,000 acre‑feet per year of salty runoff into the Santa Clara Slough. Beginning around 1977, that diverted water pooled in the ancient floodplain, spawning a wetland.

This oasis, spanning some 15,000 acres of thigh‑deep marsh, is now a recognized Mexican biosphere reserve and a sanctuary for migratory birds journeying the Pacific Flyway. But it faces an uncertain future.

The Yuma Desalting Plant was built to treat Yuma’s salty agricultural runoff but has remain unused. With water shortages needing to be addressed, there is talk of the plant being modernized and put into operation. If that happens, only the extremely salty waste product from the treatment plant would make it across the border, shrinking the wetlands, killing the cattails, and likely unable to support the fish and birds.

“If no one knows this place matters, they won’t notice when it’s gone,” says local ecologist Juan Butrón‑Méndez.

From the Rockies to Tijuana

Mexico receives 1.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water annually under the 1944 U.S.–Mexico Water Treaty. The majority — approximately 86% — is allocated to agriculture, primarily in the Mexicali Valley, where it supports irrigation for crops like wheat, cotton, and alfalfa. The remaining 14% serves municipal and industrial needs, with a significant portion supplying urban centers such as Tijuana, Tecate, and Rosarito.

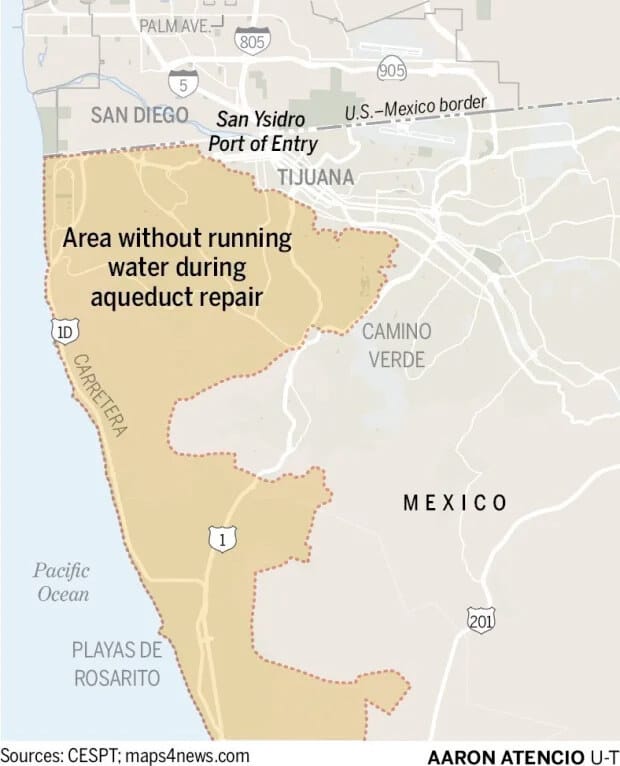

The Colorado River–Tijuana Aqueduct, a 150-mile system of canals, tunnels, and pipelines, conveys water from the River to Tijuana from the Arizona border, delivering over 90% of the city’s water supply.

Tijuana’s cattywompus municipal water system has failed to keep up with sprawling residential growth, leaving many residents with trucked-in water deliveries that cost nearly $100 per month. And the city’s total water supply is strained by a prolonged drought and growing population.

Major portions of the city experience water outages during pipeline and aqueduct repairs, which can last from a few days to a few months in some areas. These supply shortages and delivery outages require emergency water deliveries from the U.S. The emergency water comes from the Colorado River and counts against Mexico’s allotment, but it’s channeled by a different route, California’s aqueduct, arriving in Mexico at the San Diego border.

Withholding these emergency deliveries is how President Donald Trump strong-armed Mexico into making good on their obligated water deliveries to Texas from the Rio Grande last month.

They call it the “hardest working river” for a reason. And we’ve been pushing this old man past its limits.

Where will the needed water cuts happen?

Can the Colorado River Delta be afforded water deliveries after the 2026 management restructuring?

Actor Will Ferrell has an idea.

Instead of bringing more water to the delta from the River, bring water in from the Sea of Cortez. It’s Gail Griffin-level genius. Though Robert Redford disagrees.

Ok, today’s field trip isn’t over yet, but everyone needs to get back on the boat because we’re heading up the Colorado to see what’s happening on the American side of the River.

Make sure to pay the boarding fare!

On Wednesday, Trump’s Department of the Interior decided to extend many of the “system conservation” contracts for Colorado River water. As previously reported, Tribal communities and other water users have been paid by entities like the federal government to leave some of their Colorado River water in Lake Mead. The DOI expects the renewed contracts to conserve 321,000 acrefeet of water — more than Nevada’s entire allotment, and enough to fill five feet in Lake Mead’s elevation.

Meanwhile, with no visible progress being made toward an interstate compromise on post-2026 River management, independent voices are weighing in.

A coalition of academics and retired policymakers have written a letter to remind state negotiators of the need for “shared pain” and “enforceable reductions” among the Basin states. They also warn that, going forward, the states cannot depend on voluntary agreements with the federal government to subsidize water conservation. Representing Arizona in the coalition is Kathryn Sorensen from the Kyl Water Center at ASU who was formerly Director of Phoenix Water Services.

“The Post-2026 Colorado River management framework cannot assume that federal taxpayers will reimburse Western water users over the long term to forgo the use of water that does not exist,” the authors write.

On Tuesday, a group of NGOs led by the Natural Resources Defense Council sent a petition to the Department of the Interior, requesting tight federal regulation of water resources. The groups are appealing to “Part 417 of the Code of Federal Regulations,” which they say obligates the DOI to make sure water deliveries to the Lower Basin states do not exceed what is “reasonably required for beneficial use.” They’re calling for a public stakeholder process to create clear protocols for determining what constitutes “beneficial use” and make suggestions like requirements that agricultural water users adopt the most water-efficient irrigation technology.

“In short, the risks to the Colorado River water supply are unprecedented in their scale and gravity, and pose a uniquely severe threat to all those who depend on the waters of the Lower Basin,” the petition states.

Writing for Economics Observatory, Sam Bickel-Barlow says that better water pricing would go a long way in places like Arizona where data centers are getting water at very low prices. He points to China as an example, where updated water laws have created a fee system for water use and reduced agricultural water use by 20%. And researchers from the University of California have just published a study to guide Colorado River management toward region-specific consideration of the water’s local economic value.

All the while, President Trump still hasn’t installed a Commissioner to lead the Bureau of Reclamation, the agency that oversees the operation of dams and canals like those on the Colorado River.

Mother Nature has a say in all this too, and it’s not complimentary. Snowpack runoff that feeds the Colorado River is at historic lows, 55% of average rates. And the snow is melting at record rates early in the season, which will lead to greater fire risks in the summer. Researchers have just published analyses of how the snow’s melting process is accelerated by dust, blown in from the agricultural areas on the Colorado Plateau, settling on the snow and increasing temperatures.

And what about those who make the River their home? An “aquatic nuisance” has been spotted in the Upper Colorado for the first time — the “rusty crayfish” — a big concern for wildlife managers who say this beast from the Ohio Basin can overtake the Colorado’s native crayfish species. Local agencies are also busy this month looking for signs of zebra mussels, an invasive species first detected in the River last July. And a group of students in Grand Junction just helped to reintroduce the endangered razorback sucker fish to its native Colorado River habitat.

“They’re the vacuum cleaners of the river, so when dead, organic material falls to the bottom of the river, they’re the ones that are in there cleaning it up and providing valuable nutrients,” science teacher Patrick Steele told KKCO11 about the razorback fish.

On Capitol Hill, Senators Ruben Gallego (D-Arizona) and Tom Cotton (R-Arkansas) have introduced the bipartisan Water Cybersecurity Enhancement Act, aimed at expanding protections under the Safe Drinking Water Act to bolster community water systems against foreign hacking threats. The legislation follows reports that Chinese officials privately admitted to orchestrating cyberattacks on U.S. ports, airports, and utilities, possibly as retaliation for American support of Taiwan. Federal warnings earlier this year also highlighted threats from both Chinese and Iranian hackers, and in January, Russian operatives caused a water tower overflow in Muleshoe, Texas. The proposed bill would provide grants, training, and technical assistance to help local utilities strengthen their cyber defenses.

At Arizona’s Capitol, lawmakers have passed a bill requiring schools to teach kids about a body of water called “The Gulf Of America” and not “The Gulf of Mexico,” reports Capitol scribe Howie Fischer. The bill will soon confront “The Veto Pen of Hobbs.”

And there are four days left to submit applications for the City of Phoenix’s new “Love Your Block Grants” which will award $5,000 for neighborhood improvement projects addressing water conservation and sustainability. The application deadline is Monday, May 12, at 5 p.m.

The Water Agenda is currently financed by the Arizona Agenda out of pocket. That won’t last forever. To make sure it keeps publishing, consider pitching in.