In sixth grade, I developed the habit of stealthily reading books during classes, and I had two favorite books that year. Robb White’s “Deathwatch” was a relentless page-turner set in the Mojave Desert that I literally could not put down until I finished it at 2 a.m. The other became my all-time favorite work of fiction: Frank Herbert’s “Dune.”

If you’ve read Dune, or saw the recent film adaptation, you’ll be familiar with the concept of the “stillsuit,” a full-body garment that recycles moisture from the wearer’s perspiration, urine and feces. Developed by the native Fremen people of the harsh desert planet Arrakis, this technology reduced bodily moisture loss by 99.95%.

Well, as J.G. Ballard put it: “What the writers of modern science fiction invent today, you and I will do tomorrow.”

You’ve probably heard about Arizona’s new “Advanced Water Purification” rules for recycling industrial and municipal wastewater right back to your kitchen faucet. Today we’re taking a closer look at those rules, and how cities are planning to implement them.

A novel concept

Advanced Water Purification (AWP) is Arizona’s survey-approved rebranding of Direct Potable Reuse (DPR) water treatment. That consumer survey surely didn’t list DPR’s informal nicknames like “toilet to tap” or “H-Poo-O.”

The rebranding is just one of many strategies that water providers throughout the state will be using to encourage Arizonans to get over the “ick” reaction to treated wastewater.

Another strategy will be the refrain “this technology isn’t new,” which is a half-truth. The individual purification technologies are nothing new, but putting them together to treat sewage water for potable use is pretty darn new.

The City of Phoenix’s webpage about AWP shows a map of potable reuse treatment facilities throughout the U.S.

But the map is misleading.

With one exception in Texas, none of the treatment facilities on this map are actually putting treated wastewater back into potable water systems. Most of them are “indirect potable reuse” facilities which move the treated water into aquifer recharge facilities or toward other non-potable uses.

In fact, there are only three active DPR facilities on the planet that are tied into potable water systems: Big Spring, Texas, since 2013; Windhoek, Namibia, since 1968; and Beaufort West, South Africa, since 2011.

Given the success of those existing DPR projects and the increasing water scarcity in the Southwest, Texas and Colorado adopted general DPR treatment rules in 2022, followed by California in 2024, and Arizona in March of this year.

It was never going to be the most popular concept, but a more diverse water portfolio makes communities more resilient to water shortages, like those which Arizona and neighboring states will face in the aftermath of Colorado River negotiations.

The path to AWP

As Arizona Department of Environmental Quality was drafting the state’s DPR rules, one of the most common questions it got from water providers (as in letters from City of Phoenix, City of Flagstaff, Scottsdale Water) was why they were imposing costly treatment and monitoring requirements that go beyond the existing requirements of the federal Safe Drinking Water Act.

“Scottsdale does not agree with the required monitoring for an unlimited or unspecified list of Tier 2 chemicals. These chemicals are unregulated and therefore are not required [to be monitored] under any federal program for drinking water, or direct potable reuse,” per Scottsdale Water.

“The verbiage that is used, ‘robust inspection program,’ has us worried about what ADEQ intends on setting up for inspection guidelines,” per the City of Flagstaff.

Some complained that requirements for public warning systems, operator certification requirements, and general treatment requirements were burdensome, costly and unnecessary.

In contrast, the City of Tucson didn’t give much pushback to the proposed rules, but did suggest that ADEQ implement a sliding fee schedule for smaller water utilities, and partner with the state’s Water Infrastructure Finance Authority to help those utilities finance AWP development.

The Flagstaff Water Group, a “team of five retired scientists and engineers,” sometimes joined the water utilities in pushing back on ADEQ’s stringency, but elsewhere asked for a broader scope of considerations:

“We believe that human health impacts must not be the only factor in assessing hazardous chemicals. Environmental impacts on other organisms must be considered, too. … We believe domestic sources of contaminants must be included in the evaluation (e.g., personal care products, pharmaceuticals),” they wrote.

ADEQ responded to public comments and questions in a comprehensive paper and an hour-long presentation from Karthik Kumarasamy, the principal engineer who led the rulemaking process. On many points, they stuck to their guns:

“Concentration of trace organic contaminants in treated wastewater is generally higher than conventional sources used as raw water for the production of drinking water. Hence, to achieve a similar water quality outcome, a different approach for TOC management than what is required under the Safe Drinking Water Act is necessary,” they wrote.

In other cases, ADEQ modified the rules in response to the feedback:

“ADEQ has updated the Public Notice process so that public notification or public reporting will only be required if an exceedance occurs and the water is distributed to the public.”

The AWP rules

If you want to read the 40-plus pages of the adopted rules, you can do so here. Be ready for a lot of acronyms, esoteric verbiage, and technical jargon, like the following:

“An AWPRA applicant must identify AWTF-specific AOP challenges, such as the scavenging of hydroxyl radicals by carbonates, bicarbonates, nitrites, nitrate, bromides, Natural Organic Matter (NOM), pH and UV light absorption. If comprehensive pilot testing is not conducted (e.g., shorter timelines or limited scope), an AOP treatment process shall be demonstrated to achieve at least 0.5 log removal of 1,4-dioxane.”

But you probably want the Advanced Water Purification For Dummies version, and we’ve got you covered.

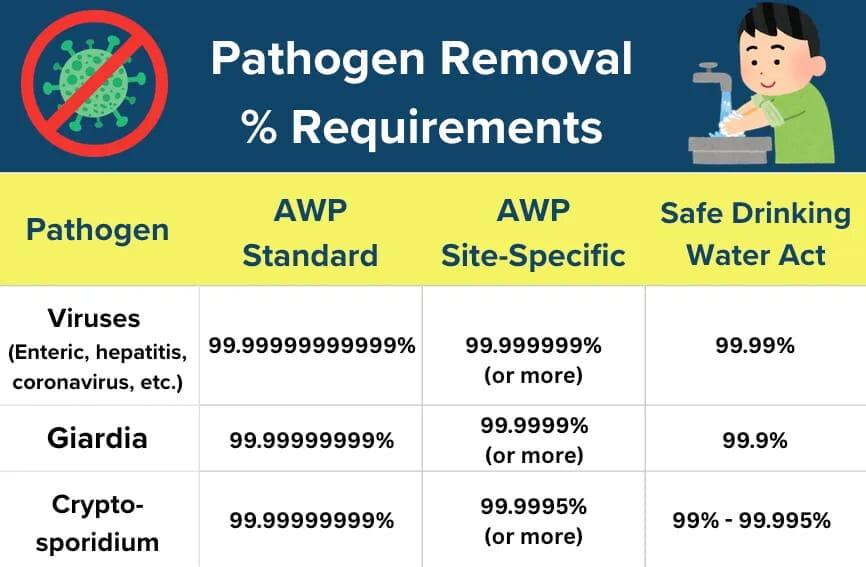

The first question most people might have is about the process of getting the yucky stuff out of the water. And unlike some of our water utility managers, most will probably feel better knowing that AWP facilities will need to purify wastewater more intensely than is required by the federal Safe Drinking Water Act.

For viruses and protozoa, ADEQ’s standard requirement is far stricter than federal requirements. But AWP facilities can also be rated for slightly less stringent requirements if they comply with a 24-month monitoring program that shows negligible pathogen concentrations.

One question I had was why these requirements are structured as reduction percentages rather than concentration measurements. A main reason is that concentrations are so low after being purified to these extreme standards that it’s nearly impossible to detect pathogens and chemicals at all.

Speaking of chemicals, in addition to all the “Tier 1” chemicals regulated by the state and federal government, ADEQ requires AWP to treat unregulated “Tier 2” chemicals like PFAS, which are known to be hazardous to human health.

AWP facilities are also required to remove nitrates and other organic compounds.

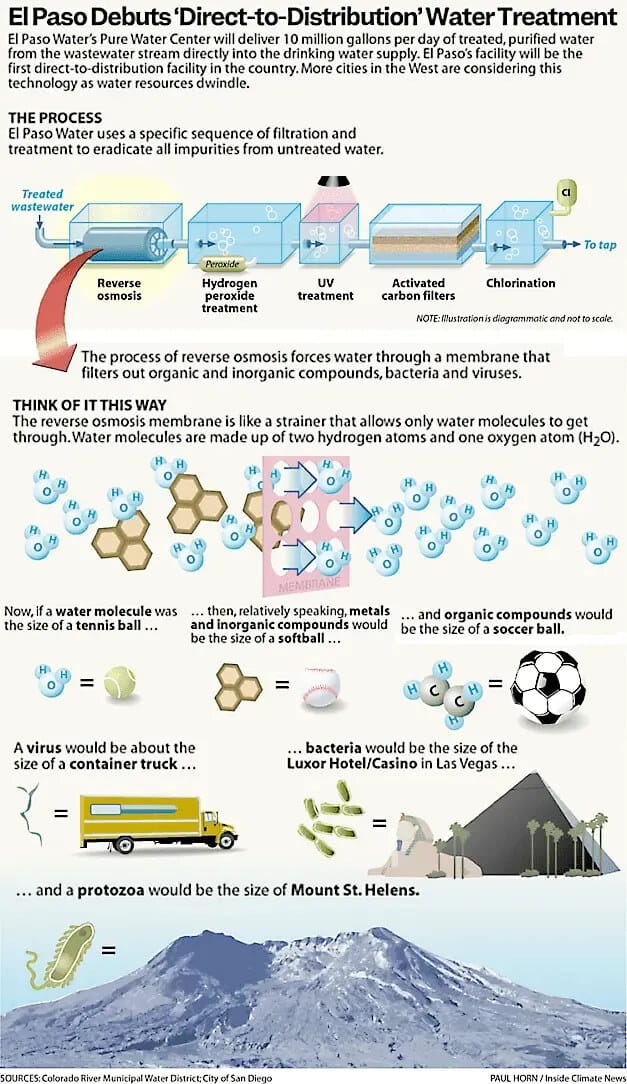

So, what technologies will do all this filtering and purification?

ADEQ has some general and specific requirements, including:

Ultraviolet light treatment to destroy microorganisms

A secondary pathogen filtration process

An oxidation process to break down chemicals and organic compounds

Two additional processes to eliminate chemicals, including a filtration membrane (such as reverse osmosis)

These multi-process “treatment trains” must also include continuous monitoring systems that can halt water distribution if contaminant levels ever exceed regulatory limits.

Finally, a Catholic priest blesses the water on its way to the municipal system. (Just kidding.)

What do the citizens think?

Of those who weighed in, 70% responded that they were likely to partake of advanced purified water.

Boldly voicing the sentiments of the 12% who are “not at all likely” to drink the stuff is Larry Gaydos of the KTAR radio show Outspoken.

“It doesn’t matter how many filters you put it through. It’s still toilet water. I may not be able to taste the difference, but I’m going to know where it came from. … And I won’t drink the water in Scottsdale because they drink H-Poo-O out there. It’s been done for 20 years.”

(Scottsdale recharges its aquifers with Indirect Potable Reuse water, but they don’t yet have Direct Potable Reuse in their municipal water system.)

Of the 303 public comments submitted to ADEQ, most were technical questions and suggestions from water utilities, but some citizens chimed in with support and criticism.

Alex Arnold: “I think it’s an amazing idea to progress the water purification processes in Arizona and influence the rest of the country.”

David Gapen: “This is vile. I don’t ever want my kids drinking or bathing in human waste, nor do I trust the science behind it to be without mistakes. This cannot pass or I will vote against every single person involved with the process.”

Karl Flessa: “Move ahead on these rules. Other states have done so already. AWP will be an important source of water in Arizona’s future.”

Julia Kessler: “As a nurse, I am very concerned about how honest and transparent the individuals in charge of testing this water will be, as SO many diseases can be transmitted this way. Honestly, if this passes, I’m going to just buy bottled water, which in turn would also be bad for the planet due to plastic being used.”

Some comments brought up interesting considerations.

Anonymous: “Judging by the lack of response to my comments of December 1, 2023, ADEQ does not feel compelled to address the cultural and religious aspects of consuming effluent as a drinking water source.”

Edward Besserglick: “Where do contaminants that are removed from wastewater go? … Bacteria and viruses can be killed. But things like PFAS are just now starting to be recognized as problems.”

From ADEQ’s response to Besserglic: “In terms of solid residue, i.e., biosolids, current regulations governing biosolids will dictate beneficial use or disposal. Biosolids are currently allowed for use as a fertilizer and are federally governed by the Part 503 rule.”

Indeed, biosolids are sold to farmers as fertilizer, but that might lead to contaminants getting back into the water and food supply by another route. As we reported earlier this year:

“No wonder the American Farm Bureau Federation enthusiastically supported Trump’s appointment of Brooke Rollins as USDA Director. Big Fertilizer has been selling PFAS-laden biowaste fertilizers to unwitting farmers.

But then, you might expect Rollins would be more concerned about agricultural pollution issues, given that her mother, a Texas congressional representative, proposed a bill in December to create regulations on PFAS in fertilizers, after learning of the health impacts these chemicals have had on local Texas farmers and their livestock.”

What are the cities doing?

Phoenix is developing the Cave Creek AWP facility that will produce 8 million gallons of purified water every day, and is expected to cost $300 million to develop.

They’re also planning for a regional AWP facility that will produce 50 to 80 million gallons of purified water daily, servicing the city along with Scottsdale and other local areas.

Tucson is also developing an $86.7 million AWP facility to produce 2.5 million gallons of purified water daily, which is about 2% of the area’s daily water demand.

But Tucson isn’t paying for it. In exchange for leaving 56,000 acrefeet of its Colorado River allotment in the River system over the next decade, the U.S. Department of the Interior is footing the bill. That’s 18.2 billion gallons of river water, or 20 years’ worth of water from their AWP facility.

That may seem like a long timeframe to get a return on their investment, but with Arizona’s Colorado River water rights on the chopping block, it may prove to be a very smart move.

Arizona’s growing fast, and every new bridge, school, and neighborhood we build should reflect the best of us.

That means hiring skilled local workers, paying them fair wages, and giving them careers they can be proud of. When we invest in people, the work lasts longer, the projects run smoother, and our communities grow stronger.

Let’s build Arizona’s future with dignity and pride — and make every job one worth keeping.

Learn more at Rise-AZ.org.

Did all that rain we got this month make a dent in Arizona’s water shortage? How big of a deal is rain, anyway? And now that we’re talking about it, why don’t cities create huge rainwater harvesting systems?

Brush up on your rainwater knowledge with a Q&A with Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University.