Two summers ago, state officials decided the aquifers in the Phoenix area and Pinal County didn’t have enough groundwater for more homes to be built.

It was front-page news for weeks as housing developers all of a sudden found out they couldn’t keep building subdivisions in two of the fastest-growing areas in the state.

But officials like Gov. Katie Hobbs were firm. There just wasn’t enough water to keep allowing more subdivisions to go up, they said.

This wasn’t the first time housing developers had sparred with Arizona officials over water, of course. But it sparked a legal battle that continues today, and could foreshadow further executive action by Hobbs to bypass the Legislature.

A year after the halt to construction, the state started making new rules to allow water providers to get around the new restrictions.

The big one was allowing water providers to offset their groundwater use by pulling it from other sources, which could open the door for housing construction to resume.

Since then, the backlash to those two decisions — to clamp down on housing development and then push for new rules — has been making its way through the courts.

The Home Builders Association of Central Arizona claim officials are illegally hamstringing development while the state is in the throes of a housing crisis.

But Hobbs pointed to the state being in the throes of a different crisis: a water shortage. And her office says powerful economic interests are trying to undermine the state’s groundwater protections.

As of this month, the parties in both lawsuits have made their cases before the court. A judge has yet to rule on them.

In the meantime, we wanted to dig into the stakes of the two lawsuits, outline how we arrived at this point, and discuss what might come next. (Also, this allows me, a grad student in environmental studies, to flex the fact that I received a hard-won A-minus in water law last semester.)

Assured water supply

If you’re water nerds like we are, you’ve probably heard “assured water supply” more times than you can count.

But the uninitiated are going to need a refresher.

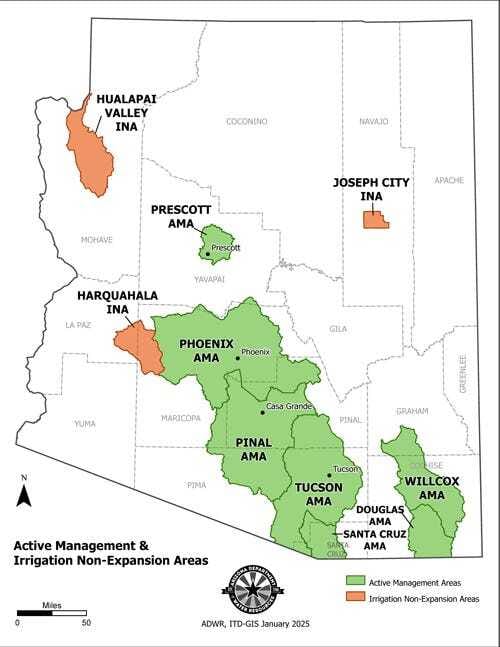

In 1980, Arizona passed the Groundwater Management Act, a forward-looking law that established Active Management Areas.

The state would restrict development within those areas unless developers could show they had enough water for at least 100 years. (That 100-year timeframe isn’t exactly scientific, but nevertheless demonstrates the long-term dependence of Arizona’s economy on access to water).

In practice, developers need to show they have enough water if they want the go-ahead from the state Department of Real Estate to begin selling houses.

They also need to show the groundwater will be withdrawn from depths not exceeding about 1,000 feet.

There are two kinds of assurances at play here.

For most residential construction in the Phoenix area, developers can receive a written assurance of availability from a designated water provider, whether it be a city or water company. That’s good enough for the state to OK construction.

But if they're not within the service area of a designated water provider, the developer needs to do the work to receive what’s called a certificate of assured water supply.

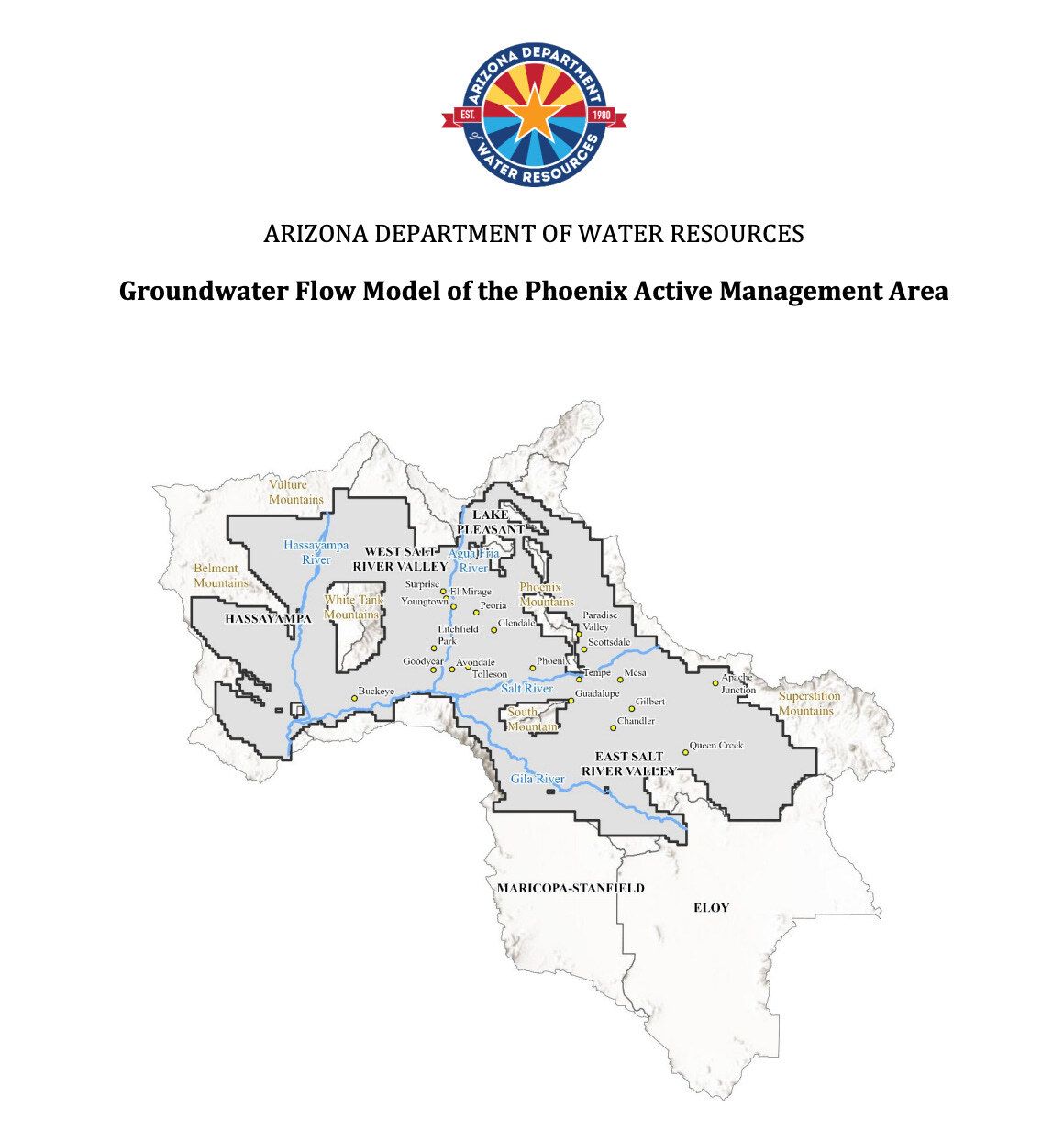

That’s why the state’s construction moratorium applies to fast-growing exurbs like Buckeye and Queen Creek, and not downtown Phoenix. The exurbs are outside of the service area of municipal or regional water companies and must rely on groundwater.

The state’s June 2023 update to its assured water supply model comprised a couple of major findings.

For one, there will be an unmet demand for 4.9 million acre-feet of water over the next 100 years.

The state also found wells that violated the 1,000-foot-depth-to-water limit.

That was enough for the state to stop issuing certificates unless the developers could find a source of water outside the aquifer, which was getting harder to do, especially with Colorado River cuts on the horizon.

The state didn’t issue a new rule. Instead, officials said they were exercising their statutory and regulatory power to protect Arizona’s water resources in a time of “unmet demand.”

The Arizona Department of Water Resources said “unmet demand” referred to the amount of groundwater that would be needed, but would no longer be available, after wells run dry.

So developers would need to show “existing and assured water supplies” if they wanted to satisfy state officials.

Lawsuit No. 1: Faulty premise

In effect, officials said they wouldn’t approve new certificates for subdivisions because those certificates would be based on a faulty premise — that water would be available over 100 years.

To the homebuilders, that meant if wells ran dry anywhere in the area, they would have to halt their housing project, even if, in theory, there was water available immediately underneath the proposed site.

The homebuilders argued that they now have to somehow prove that the depth-to-water won’t exceed 1,000 feet anywhere in the Phoenix AMA, which is a huge area.

They also took issue with the fact that “unmet demand” is not defined in state law.

And the fact that we’re talking about housing here — as opposed to agriculture or data centers, which are not affected by the unmet demand determination — is important. Arizona, as much as it is experiencing a water crisis, is also experiencing an affordability crisis.

And to some — especially those who stand to gain financially from development — building new houses is a way out of that crisis. And officials should get out of the way.

“Decisions on vital statewide concerns like the availability of affordable housing and the responsible stewardship of our natural resources should be made through a transparent, democratic process — not imposed by executive fiat,” Jon Riches, vice president for litigation at the conservative Goldwater Institute, which is representing the plaintiff in the case, said in a January statement.

ADWR dismissed those arguments, and asked Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Scott Blaney to throw the case out in March.

The state says that what the builders want — for decisions about water availability to be made only where they plan to build — defeats the purpose of the state’s groundwater laws.

State lawyers argued that if builders got their way it would lead to a “catastrophic cost to water supplies” for everybody who’s already using groundwater.

“The suggestion that the Legislature tasked ADWR with assuring a water supply for new subdivisions for at least 100 years but did not intend ADWR to consider threats to the water supplies for current users and issued determinations in the area is absurd,” lawyers for the state said in court.

A judge has yet to make a final ruling in that lawsuit.

Alternative pathways

Last year, the state adopted a new rule, based on a recommendation from the governor’s water policy council, that provides an alternative pathway for water providers to show they have an assured water supply.

That pathway would act as a release valve for areas that might otherwise not see new construction because of the unmet demand determination.

In short, the rule says a provider can obtain the designation by finding an alternative source of water, like treated effluent, and by reducing its groundwater use by 25% of the volume of the new water from the alternative source.

So a provider that gets 5,000 acre-feet of new water could use 75% of that water to meet its needs and the remaining 25% to offset its groundwater use.

Providers like EPCOR and Arizona Water Company have already started using this option, according to the state.

“We're really again allowing homebuilding to go forward, which is important, but we're doing it in a responsible way,” ADWR Director Tom Buschatzke told ABC15 in March.

Lawsuit No. 2: A tax by any other name

The second lawsuit also is heating up.

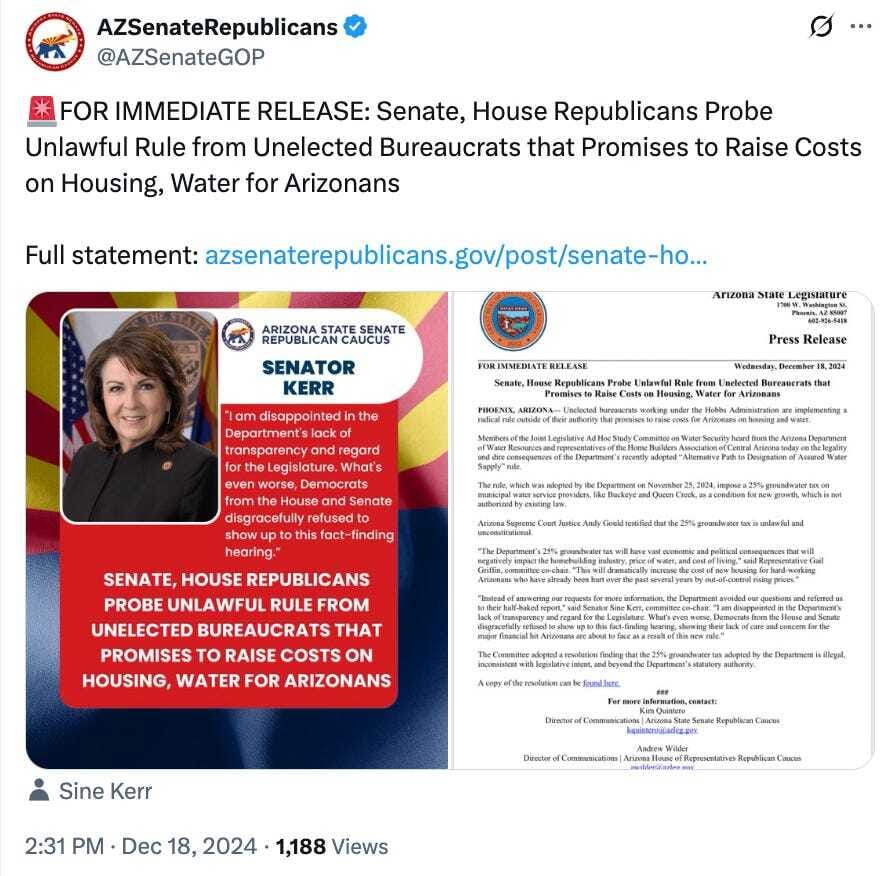

The alternative pathway didn’t satisfy the homebuilders association or its allies in the Legislature, Republican leaders Warren Petersen — himself a homebuilder — and Steve Montenegro.

In March, the trio sued the state, this time represented by attorney Kory Langhofer, instead of the Goldwater Institute.

They argued the new rule was hastily and improperly adopted without adequate stakeholder input and economic impact analysis. Moreover, through some math of their own, they reinterpreted the technically optional 25% offset as a “redistributionist 33.3% water tax.”

Much as in the other lawsuit, they argue the rule improperly requires builders to consider water outside the immediate use of their proposed development.

And because of the regulatory environment in Phoenix, they argue that the rule is not in fact optional.

The rule “forces new groundwater users (such as developers) to obtain water to compensate for ADWR’s projected deficits caused by the historic uses of other users,” they wrote.

“The people of Arizona elected us to defend their interests, not allow unelected bureaucrats to impose illegal taxes that make the American Dream of homeownership even more out of reach,” Montenegro said in a statement at the time of the lawsuit’s filing.

What they dubbed the “33.3% groundwater tax” was a “blatant overreach of executive authority,” as well as an “attack on hardworking Arizona families” who would watch housing prices jump by thousands of dollars.

The lawmakers also didn’t want the governor to “trample on the authority of the Legislature.”

The state argues the new rule doesn’t fundamentally change the supply designation requirements. It just provides an alternative.

The lawmakers and homebuilders association were trying to flood the court with “misleading labels while studiously avoiding the statute that governs this case,” state lawyers argued.

But calling the new rule a “tax” to make a political point doesn’t change the fact their claims don’t hold water, they argued.

Plus, the new rule only applies to water providers, not homebuilders. State attorneys urged the court not to believe “speculation” about the possibility of increased home costs at an “unspecified future time.”

But the homebuilders say the rule will “obviously escalate development costs.”

They further argue that legislators have standing, in part because lawmakers considered legislation that would effectively kneecap the rule.

Again, a judge has yet to rule on the case, and the rule stands, for now.

An insane world

The department’s actions generated a flurry of GOP legislation attempting to end the moratorium and prevent the new rules from taking effect.

As is often the case in our new water reality, their bills uniformly fell before Hobbs’ veto pen.

On top of that, the Legislature couldn’t come together on comprehensive groundwater reforms this session.

At the governor’s office, they’ve said the lack of reforms could lead to a special session, and maybe further executive action, like Hobbs did when she created a management area in the Willcox basin last year.

Can you guess what likely would follow that executive action? That’s right, more litigation.

Resolving these crucial issues through the courts is far from the best way to make policy, Arizona Republic columnist Joanna Allhands wrote in February.

“In a saner world, these major players would broker compromises on how to get there, instead of taking unilateral actions that begat other unilateral actions in response,” she wrote. “But that’s how water politics work these days. And so here we are, now effectively legislating by lawsuit. The problem with court orders is they create winners and losers, not the compromise necessary to find solutions that work for everyone. They are the last thing we need.”